This article originally appeared in Love and Regeneration. It was edited for length and style.

Our bodies crave nature — of this we are sure. We are all familiar with the innately restorative effects of a deep breath of fresh air. We bring fragrant bouquets into our homes, hoping to waft the scents of nature into our sterile spaces. We walk out into the world, jump into lakes and streams, and plant herbs in our backyards. And until recently, we had little but our intuition to back this up, confirming how good it feels to interact with the natural world as part of our natural heritage.

The last few years have shown a rise in scientific and architectural interest in our relationship with nature, a topic known as biophilia. Edward O. Wilson coined the word in his 1984 book of the same name. He described it as “the innate tendency to focus on life and life-like processes.” We are meant to engage with the natural world, for the health and benefit of our bodies, our minds and our communities. We’ve known for some time that a lack of access to natural ecosystems is an impoverishment for humankind, and we are finally beginning to produce hard data to prove it. Access to nature – along with clean air and water – must be recognized as a basic human right.

Stephen Kellert, a friend and colleague, was a pioneer of biophilia and wrote the 1993 book The Biophilia Hypothesis. In this critical text, he names a “human dependence on nature that extends far beyond the simple issues of material and physical sustenance to encompass as well the human craving for aesthetic, intellectual, cognitive, and even spiritual meaning and satisfaction.”

Kellert wrote, “This daring assertion reaches beyond the poetic and philosophical articulation of nature’s capacity to inspire and morally inform to a scientific claim of a human need, fired in the crucible of evolutionary development, for deep and intimate association with the natural environment, particularly its living biota.” With his recent passing, we revisit his work and add some new thinking to the emergent field of biophilic design.

The initial rubric

When I wrote and published the Living Building Challenge in 2006, it became the first green building program to include biophilia as a dedicated topic. The field was still quite young and barely defined beyond a general thesis. We included biophilia for two reasons: to elevate the level of discussion among practitioners and to use the standard as a way to help advance the topic. We knew that getting designers to think intentionally about our relationship with nature was a critical first step and that we could use LBC to shine a light on critical issues under-appreciated within the green building world.

Our initial biophilia requirements put forth Kellert’s original design principles and encouraged an awareness of our own connections to life and “life-like processes” through design. The parameters were simple and loosely defined – the topic was so new, and we wanted to get people thinking and learning collaboratively with our project teams. The industry’s understanding of biophilia has evolved significantly since — our decision to include biophilia as a topic was timely.

However, there has always been a degree of confusion surrounding the implementation of biophilic design into architecture. Though more project teams began to discuss the topic of biophilia, and some project teams did begin to break new ground on integrating nature into the built environment, conversations rarely broke through a surface-level understanding. People worked to meet the letter of the standard and no further. Or they jumped to immature conclusions, believing that they could simply decorate their way into Biophilia, practicing business as usual by shrubbing up their buildings, and by throwing in a small living wall into their lobby and some patterns on their walls.

These shortcuts – though well intentioned and perhaps better than no focus on the subject – skipped over the underlying philosophy: that our society needs to radically improve and deepen our daily interactions with the world outside of our walls precisely because we are now so separated from it. A veneer of nature alone is wholly inadequate.

Recent versions of the LBC standard changed the approach and emphasized the need for the teams to engage more deeply with biophilia. The hope is that a greater interdisciplinary focus on the subject would help to mature the biophlic designs and elevate the nature/human connection more authentically.

The jury is still out.

Biophilic design versus biophilia

Let’s revisit for a minute why the subject of biophilia and the subcategory of biophilic design even exist. Like so many movements, the field of biophilia is a reaction to a great loss of some kind. The environmental movement was born from a response to the destruction of the environment witnessed by individuals and communities (think Rachel Carson, City Beautiful movement, Earth Day). The social justice movement exists because of rampant inequalities in our societies; without injustice, no social justice movement would emerge.

Biophilic design is the natural response to a rapidly growing lack of connection to the natural world experienced by so many urban dwellers. When we spend most of our time inside sterile and life-impoverished spaces, we find ourselves lacking the enriching, inspirational and restorative effects of nature in ways we are only just now beginning to understand. The impacts are developmental, cognitive and physical, with implications ranging from healing ability to vitamin D production to mental health.

We must distinguish biophilia from biophilic design. Biophilia describes our innate desire to connect with living things. Biophilic design is the response from the architectural and design communities to the topic of biophilia and to the need for more purposeful interventions.

rELATED STORY

rELATED STORY

How one Living Building approaches biophilic design

One can’t imagine farmers, ranchers or particularly indigenous people in traditional lifestyles needing to invent a field like biophilic design a couple centuries ago. They already lived with an abundance of nature. Before the Industrial Revolution, the topic would have seemed laughable. It’s important to recognize that the field exists only now to limit the damage done with our current community and building designs, and the degree to which we’ve separated from most life in the last few decades.

Most urban residents currently experience what Richard Louv famously referred to as “nature-deficit disorder.” The variation in the magnitude of such a deficit depends on the character and intensity of the urban context. Most people are now so under-stimulated by nature in their urban lives that we can no longer derive our necessary exposure to the diversity of life required for basic health from our daily routines. As a result, we must deliberately and surgically add it back into the rhythm of our lives to restore in some measure a balance that has been lost – or so goes the theory.

On top of the under-stimulation from natural processes and life forms, we are assaulted with a constant overstimulation from our built, mechanical world, which taxes our senses in completely different ways than we are evolutionarily accustomed to. We are growing deaf to our own biological input as we overwhelm our senses with the sights, smells and sounds of modern life. Humanity is simultaneously under-stimulated in critical ways and overstimulated in destructive ways.

Living in our well-lit, air-conditioned spaces and enjoying the fruits of our comfort, we can delude ourselves into thinking that our move toward sterility and artificiality has been our inevitable trajectory – that we are programmed to fear nature – when actually the opposite is true. We are a species that is drawn to life and flourishes in its presence. We experience this on an individual level every day when we take a deep breath upon stepping outside. I sometimes joke that in one regard smokers are healthier than non-smokers in that that they take more frequent breaks and step outside more than others. All of us should practice this … while skipping the tobacco.

As more scientific evidence emerges to back up the hypothesis of biophilia, we recognize how intuitive the outcomes are. None of this is surprising when we think back on the fact that our ancestors spent most of the last 200,000 years immersed in a daily struggle in nature – and only the last couple hundred years in a form of nature deprivation. We are a species that evolved out in the world for almost all of our existence, and just recently walked inside, washed our hands and shut the door. We evolved under the stars, out in the rain, under the trees and in the fields. We evolved surrounded by life. Our bodies are wired to connect with other living things to the extent that without them we are truly diminished.

Of course, a lot of these things killed us, ate us and made us sick – such was the cycle of life. But the good and the bad came as a package, something we should have been more sophisticated to realize. As the rate of technological innovation accelerates, so grows our separation from the natural world. Technology has given us greater security, comfort, hygiene and longevity, but has left us with an intense sensory deprivation whose consequences we are only beginning to appreciate.

It stands to reason that we can’t simply apply token nature elements and expect them to overcome the huge shift away from the natural world our lives have taken. And we need to recognize that interior design, or for that matter design in general, is not enough. Healthy living requires intense interactions for prolonged periods in actual nature on a regular basis. Or it means bringing nature authentically back into our cities so that we are once again connected to life continuously in the background. What we can do inside buildings with surface application will always be secondary to simply going outside, walking in parks or hiking in the woods surrounded by as much biodiversity as possible.

Scientific evidence catches up with intuition

Writers, planners and philosophers alike have posited that there are benefits associated with exposure to nature. Frederick Law Olmstead, William Wordsworth, Ralph Waldo Emerson and John Muir are among those early thinkers who espoused the benefits of nature to the human experience. Through conservation efforts, the creation of urban parks, and spiritual and emotional writing, they set a stage for science to follow.

On the topic of mental health, much has been written to support the hypothesis that nature is essential to our well being. Greg Bratman, a Stanford researcher, showed changes in the brain activity of people before and after walking for 90 minutes either in a large park or on a busy street in downtown Palo Alto. He found decreased activity in the subgenual prefrontal cortex (where we process depressive thoughts) in those who walked in nature. He concluded that nature “may influence how you allocate your attention and whether or not you focus on negative emotions.”

Similarly, several psychologists from the universities of Utah and Kansas studied the effects of nature on our attention spans and problem-solving abilities. They found that a four-day backpacking trip led to a 50 percent increase in creative problem-solving performance in a group of novice hikers. Their research presents a “cognitive advantage to be realized if we spend time immersed in a natural setting.”

People around the globe have leapt to incorporate this growing body of evidence into their lifestyles. Take, for example, the growing trend of forest therapy. Developed in the 1980s (likely out of necessity, given Japan’s intense urbanization), a form of forest therapy known as Shinrin-yoku has become a staple of preventative healthcare in that country. Forest therapy encourages people to spend quiet, contemplative time walking in the woods to improve their mental and physical well-being.

Many medical studies present the benefits to physical health of exposure to nature. One conducted on a 200-bed suburban Pennsylvania hospital found that post-op patients with views of nature from their windows recovered faster than those who were looking out onto a brick wall. They also had less complicated recoveries and less need for pain medication than those whose views faced the brick wall.6

Another study, by researchers in Tokyo, showed the increased longevity of elderly citizens who lived closer to public, walkable green spaces. Furthermore, it found an increase in longevity from those who lived near a space where they could stroll and those who lived near or on tree-lined streets or parks. The Japanese study marks an interesting approach to the differentiation between various types of outdoor exposure.

Despite the seemingly clear trends in countless scientific journals, many researchers struggle to draw a substantiated causal link between the noted health effects and the exposure to nature. The sticking point has been how to quantify the effects of nature.

rELATED STORY

rELATED STORY

Sturgeon: Hard to fit biophilic design on checklist

A good example of this dilemma is illustrated in “The Relationship Between Trees and Human Health: Evidence from the Spread of the Emerald Ash Borer.” This study took data from the naturally occurring spread of an invasive forest pest, which was causing a huge loss in tree populations across 15 states. It compared mortality rates with the presence of the emerald ash borer on the county level between 1990 and 2007, and found a correlation between loss of trees and an increase in mortality related to cardiovascular and lower respiratory tract illness. The study was based on observed data, however, and thus was unable to claim causality.

In a discussion of the ash-borer study, researcher Howard Frumkin articulated a primary challenge of the field: It is still unclear how to define a dose of nature. He also postulates “even the most rigorous biomedical research results would not tell the whole story. … In a world of specialized researchers and niche journals, it is the rare study that quantifies all the benefits of trees, for human health and well-being, the environment, and the economy.”

Another study, published in the February 2012 edition of the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, looked into the question of the health effects of green design on the scale of a city. Researchers found that the total area of green space in the city was not the most accurate indicator of a healthy city, in fact the inverse was true — cities with more green space had slightly higher rates of all-cause mortality. Several factors could have yielded this result (the selection bias of a greener city for the infirm and elderly, for example). But there was one that seemed far more likely than the rest: the lack of distinction in the study between sprawling, private suburban lawns and high-volume, multi-use public parks. For the purposes of quantifying “greenness,” these were counted as the same.

The outcome of that study is a lesson for scientists, planners, architects and citizens alike: that the design of our outdoor spaces is as important — if not more so — than the fact of their existence. The report plainly states that, “if we green our cities without attention to the form the green spaces take, and the kinds of contact that residents want to have with their natural environment, there may be no benefit for population health.”

Central Park is living proof of the greater power of well-designed, usable, public greenspace. By providing a huge, natural environment in the middle of New York City, Central Park serves as a nature hub for all citizens. It is host to countless events — cultural, athletic, educational, and social — and provides the city a release from the overwhelming stimuli of the urban metropolis. I’ve long posited that Central Park serves as a giant biophilic pressure relief valve, without which the city would fail to balance the intensity of the urban landscape. By comparison, a suburban compound with individual lawns — though possibly greener in area ratios — is essentially an ecological desert, not much better than concrete.

Science alone cannot answer all the questions in this field. Biomedical research, landscape architecture, architecture, medicine and many other disciplines must collaborate in order to build a nuanced and informed rubric. We must work together to grasp a full understanding of the factors at play in biophilic design and to learn how to modify modern life to be once again in balance.

There also is a clear need for new methodology to guide designers through the process of integrating biophilic design into their projects. We must pose and answer the questions that continue to crop up. How much biophilia is enough? When and where is it most critical and to whom? Clearly, there is a qualitative difference between types of exposure to nature that affect us in different ways. It’s not as simple as “greener is better.” It is vital that we make distinctions between the needs of an office worker and those of a prisoner; between the natural access afforded to people living in Scandinavia and those in the Caribbean; between the slightly positive effect of having an African violet in the corner of the office and the transformative power of a lifestyle shift that pushes us out into nature on a regular basis.

The exponential scale of biophilic design

In an effort to add to the growing field of investigation in biophilic design, I’ve put up some methodological scaffolding upon which to build future research. Let’s call it the “Scale of Biophilic Design.”

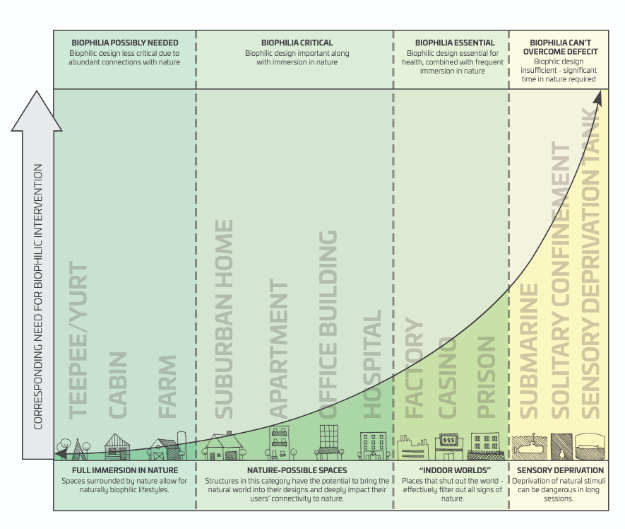

I propose that the needs for biophilic design change in quality and quantity along a spectrum that is far from linear. This non-linearity needs to be understood by the design community practicing the young field of biophilic design. As our habitats move further from the natural world, our need for immersive nature increases exponentially — so that, at each level, the need for natural immersion becomes many times more critical than at the preceding one. This scale measures the effectiveness of typical biophilic design responses against the benefit of being out in nature. As the need increases, the need for natural immersion rises. There is a gradient of quality of nature wherein a lawn is better than no lawn, but a forest or healthy meadow is better than a lawn. The quality is related to the abundance, diversity and ecological health of life present, as well as its accessibility.

People often conceive of biophilic design as something like a green Band-Aid. They assume that the introduction of a few plants makes up for a complete loss of nature. Such approaches are simplistic and far too inconsequential — they provide little value if they aren’t part of an overall lifestyle that brings us back outside an in touch with a diversity of life.

The diagram above proposes a non-linear approach to the field of biophilia. Along the x-axis is a selection of human dwelling typologies ranging from immersion in nature to total sensory deprivation. As one moves along the scale toward exposure to nature, the need for biophilic design intervention gets smaller. For example, someone who spends much of their life on a farm is not in terrible need of intentional, ameliorative biophilic interventions. If that person were to move to a suburban house, however, their need for biophilic design would grow.

The scale helps to divide typologies into categories of need. According to this methodology, there is a “sweet spot” where biophilic design can make a huge difference to the user’s lifestyle and wellness. This sweet spot is such because biophilic intervention is both possible and needed – there is an opportunity to leverage architecture to enhance biophilic experiences. As architects, spending our time enhancing the nature connection within these typologies could be the most effective use of biophilic design.

As you move to the right on the scale, you enter environments that are nature impoverished. In these cases, biophilic design moves will always be inadequate. There is a reason that seamen spend limited amounts of time on submarines and must balance that time of sensory deprivation with time spent in a more natural environment. In this case, the time dimension becomes very important. Few people spend all their time in any one of these typologies and as such, we must think holistically about our approach to people’s lifestyles beyond the one structure in question. For example, someone who lives in an urban apartment but goes out every weekend to a cabin in the woods will be exposed to far more biophilic surroundings than someone who lives in an urban apartment and spends weekends at a casino. Biophilic design then is not a cure but part of an overall treatment.

Any convention that aims to measure relative need for biophilia must address variables that have long been ill-defined: the qualitative difference between a paved courtyard and a park, the amount of time that people spend interacting with nature, and the amount of time that people spend inside or in non-biophillic environments. These variables have long eluded scientific study and will be critical in guiding the conversations to come.

A clear, qualitative biophilic scale could also help guide discussions, suggestions, requirements and implementation of biophilic design in architecture and planning projects. By quantifying the needs of a given typology relative to other projects along this Scale of Biophilic Design, designers could target their responses accordingly.

The implications of such a nuanced approach are profound. For those who work in environments where there is an extreme nature deprivation, more frequent exposure to the natural world could be of vital importance and suggest that both design and policy are required for substantial interventions. People who work in prisons, on submarines or in internally focused structures should have significant corresponding time out in nature for their long-term health and well-being.

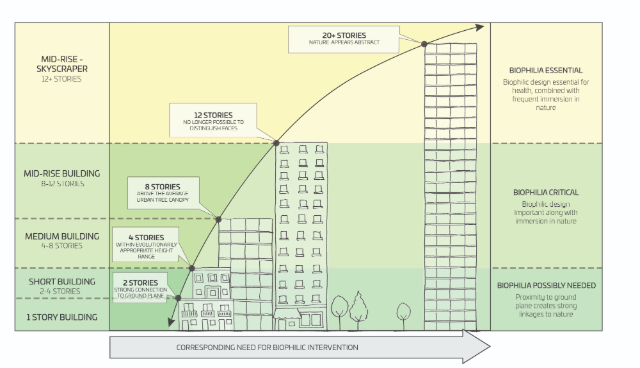

Less extreme but still critical is understanding what is required for people who spend significant amounts of time in tall buildings — away from the ground plane and separated from landscape by distance and height. As the second graphic shows, there is a decreased connection to the natural world as you move farther from the ground. While beautiful views of nature from a highrise certainly help, there is a point at which the distances are so great that the vistas become abstracted.

Beyond the separation from the natural world, there is an additional separation from human interaction. I’ve long felt that children especially suffer from living above a certain height off the ground. At 200 feet of distance, we can no longer tell one person’s face from another; at 500 feet, we can barely see the tops of people’s heads. This disassociation with other members of our species creates a disconnect when it makes up the majority of our experience at a young age.

The diagrams put forth for the first time in this article are suggestive of scale and impact and should provide a framework for researchers to test and adjust based on scientific rigor and longitudinal studies on impacts to people.

Thoughtful approaches to biophilic design will take into account the particulars of the site and the demographics of users. The biophilic needs of a space will change depending on the age of the users, the amount of time spent inside the space, the seasonal fluctuations and many more criteria. For example, the very young, the elderly and the sick are especially sensitive to the effects of natural exposure and most harmed by a lack of exposure to life. In these sensitive demographics, the need for concentrated interaction with the natural world has been shown time and again to be vitally important. Similarly, those who live in the more extreme latitudes of the world – and therefore spend less time outside – have been found to react positively emotionally and medically when they bring nature more deliberately into their daily lives.

The best investigation of the biophilic needs of a project is wide-reaching, nuanced and deep. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to biophilic design. Rather there is a range — with sweet spots that differ depending on conditions. Designers practicing biophilia would be wise to think more deeply about how to design differently. As we begin to understand the variables at play, we can adjust our responses to the context.