If any organization was nimble enough to leapfrog the race to build the world’s first certified Living Community, it had to be The Ecology School.

Drew Dumsch co-founded the school in 1998. Each fall and spring for nearly two decades, he and his colleagues rented a summer camp near Saco, Maine, where they offered educational programs — occasionally for adults, mainly for children.

The driving philosophy was “live what you learn.” A bread-and-butter curriculum turned out to be a multi-year course devised with nearby school districts. It allowed elementary students to progress from in-school outreach to field trips to “capstone” experiences. For the capstones, sixth graders would room in cabins for three or four nights while developing skills in ecological living.

At some point, Dumsch says, he had an epiphany: Ecological learning is at its heart the “ultimate systems learning” — a pedagogical approach that can help students navigate a complex, modern world.

“The ability to understand and make connections is the ability that we’ll all need to make it through the 21st century,” he says.

But a foundation in the school’s approach to education was missing. Renting facilities from a summer camp didn’t allow The Ecology School to fully “live” that live-what-you-learn philosophy. Without a place designed to impart an understanding of nature, how could students truly grasp the ecological systems in which they were supposedly immersed?

Dumsch, the school’s CEO, had long been an armchair enthusiast of green building. He turned over in his mind how the school’s own physical presence might model a more ideal world to students, how an entire campus in balance with nature could build their understanding of a healthy community, how raising and eating organic harvests could teach skills that would last a lifetime.

“At a certain point, it felt like The Ecology School’s destiny was to be a landowner — to be responsible for a piece of property and to make that property more sustainable,” he says.

Then, about four years ago, a fallow, 105-acre farm just inland from Saco, along the Saco River, came on the market. Most of the property already had been placed under a conservation and agricultural easement. The easement left an eight-acre rectangle around an old house, a barn and a chicken coop that could be developed into a small campus.

That particular piece of land in that particular location at that particular time seemed fateful.

“It was,” Dumsch says, “like a miracle.”

An unusual arrangement

In 2017, the school was able to buy River Bend Farm. By that time, board and staff members had a much better idea of what they could do with the property.

They’d consulted an agronomist who told them abandoned pastures down by the river were blessed with rich “podunk” soil, where the harvest could feed 150 visiting diners. A sustainable forestry consultant had suggested how the woods could be managed for biodiversity and selectively harvested. And the board had decided that new buildings on the eight-acre campus were going to meet the most rigorous green standard they could find — the Living Building Challenge.

They also began to look for an architect. Board members liked all three finalists. Each firm was based in nearby Portland, which was important because Dumsch wanted the project to seed knowledge about regenerative design in the local architecture community. Each already had sustainable credentials and had completed plenty of green buildings. Each seemed to get what the school was trying to achieve.

So one board member suggested an unusual arrangement — unheard of, really, for such a small project: Why not have the architects learn together while they worked together? Instead of just one local firm gaining knowledge about the LBC, the project would provide that experience to all three.

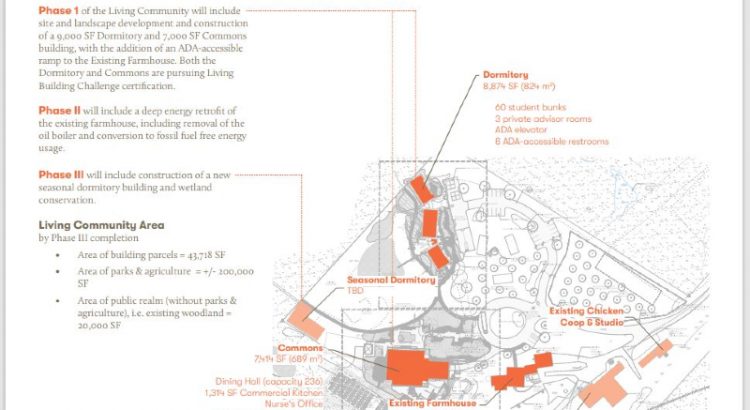

Dumsch says he could hear the architects “gasp” at the idea. But they agreed to it. Scott Simons Architects was to design a 7,000-square-foot dining commons. Briburn, would design a 144-bed dormitory. Kaplan Thompson Architects, was named lead designer, concentrating its efforts on common elements and shared services, such as developing a materials palette, and figuring out shared energy and water needs. Kaplan Thompson also oversaw the development of a master plan by Richardson & Associates, a Saco landscape architecture firm.

Jesse Thompson, principal at Kaplan Thompson and a leading Passive House practitioner, admits he was skeptical at first. But he says now that the arrangement proved to have advantages. The firms brought different strengths and learned from one another. And as the intensity of the work increased, they were able to spread out a load that otherwise might have gotten overwhelming.

“If biodiversity in nature is good,” he says, “then maybe diversity of design is good, too.”

A community in balance with nature

So far, there isn’t such a thing as a certified Living Community.

The International Living Future Institute launched the Living Community Challenge in 2014, only seven years after it kicked off the Living Building Challenge. Like the LBC, the LCC lays out a transcendent vision. Its webpage tagline reads: “Imagine a community that is as connected as a forest ecosystem.”

Also like the LBC, the Community Challenge has positioned itself as the most rigorous certification standard in its category. It requires projects to adhere to seven performance areas, or “Petals,” by fulfilling 20 hardcore imperatives. Living Communities must generate their own clean energy, treat their own water, grow much of their own food and process their own waste. Among other things, they must expand opportunities for wildlife, social justice and “human-powered transportation.”

The Petals are the same as the Living Building Petals, but the imperatives differ. At least half the number of community-owned buildings within Living Communities boundaries (or the buildings’ square-footage) must seek LBC certification. The community must include car and bike sharing, a library, recreation programs for seniors, kids and adults, and other features to promote a “civilized environment.” As with the LBC, once the entire Living Community is built out, certification will be granted only after 12 months of “actual, rather than modeled or anticipated, performance.”

No wonder the International Living Future Institute, which operates both the LBC and the LCC, warns participants that the Community Challenge is a journey — not just a destination.

The long climb toward those high expectations is surely one reason that the LCC has only slowly gained momentum. Fourteen communities have registered for the program. Two — California State University at Monterey Bay and the Reserva Santa Fe near Mexico City — have completed qualified LCC “vision plans,” one of the initial steps in the process.

ILFI Vice President for Programs Marja Williams cautions that the Living Community Challenge shouldn’t be judged by volume. Its aim, she stresses, isn’t to flood the market; it’s designed to create models toward which other communities will aspire.

“For a program that’s only five or six years old.” Williams says, “this is what we’d expect to see right now — especially for such a huge commitment.”

‘Weren’t a lot of precedents’

Dumsch insists that he never saw the Living Community Challenge as such a huge commitment. It seemed to him like an extension of what the school already was doing. Most of the farm already was in an easement (and would soon be placed in a land trust). Richardson & Associates’ master plan was complete. And two Living Buildings were in the early design phases.

“We’d already boxed ourselves in from a lot of other directions,” he says. “Adding another [certification program], at face value, may have seemed crazy. But for us it made sense. They didn’t feel like boxes. They gave us structure to succeed at the goals that we were setting for ourselves.”

The school had some advantages over other registered communities. Many of the others are larger and more complex. They include neighborhoods, college campuses, real-estate developments and even whole towns.

“The fact that the mission of their organization is so aligned with the LCC helped,” says ILFI’s Patsy Healsy, who helped review the Ecology School’s efforts. “Having single ownership of all of the land and properties that they are going to develop helped. Plus, they already had a vision of where they wanted to go, and they are really well organized.”

The school’s approach was to take on two steps at the same time — the vision plan and the more detailed master plan.

Much of the work was placed in the lap of Kaplan Thompson architect Danielle Foisy, who’d helped to coordinate the landscape master plan for the entire property. She now had to discern which information from the original plan was needed for the Living Community master plan. And she had it figure out which features of the Living Building projects already addressed the Living Community,

That, she says, involved lots of spreadsheets, collating and back-and-forth with an ILFI staff that itself had never reviewed a Living Community master plan.

“There weren’t a lot of precedents,” Foisy says. “We probably went through four rounds of revision.”

It turned out that the substance of the plan wasn’t so different from what the school and the architects already had planned.

As part of its resilience requirements, the Living Community Challenge mandates a common meeting area for emergencies; the dining commons naturally served that purpose. The school’s existing plans to use the farm as a learning space for students, as well as a source for their food, would easily meet the LCC’s agriculture component.

Because of the LCC’s ban on combustion, the school sought, and received, exemptions for an outdoor pizza oven, a maple syrup evaporator, a farmhouse fireplace and two campfire sites. As the plan explains: “The congregation around a campfire is an important aid to storytelling, stargazing, and listening to the sounds of the night.”

But Foisy says the process forced the design team to think about the big picture of sustainability, including the school’s connection to nearby Saco. A trail network was expanded, part of which will be accessible to the public. In an attempt to better link the school to the community, Dumsch wrote a letter to the town asking that a “protected bike lane” be added to the main road to school.

The plan also organizes the school’s aspirations into phases. Phase I is underway. It includes construction of the two Living Buildings, installation of roof-top and ground-based solar panels, and planting an orchard, perennial berry gardens and annual crops.

In later phases, a “seasonal dormitory” will be built to Living Building standards, additional ground-based solar panels will be installed, and the existing farmhouse (built in 1794), barn and chicken coup will undergo deep retrofits. At that point, all the campus’ electricity will be solar.

“They can never be individually perfect buildings,” architect Thompson says. “But thinking about the way they work together allowed everything to work together better.”

A trio of firsts

Last fall, construction began on the two Living Building projects.

In many ways, the dormitory and dining commons will be simple structures. The escalating costs of the hot 2019 construction market forced the architects to eliminate some flourishes, such as uniquely angled roofs on the three wings of the dormitory and a recycled-glass substrate material called Glavel. Both buildings feature the tight envelopes, thick walls and the blockish look typical of Passive House construction — appropriate to Maine’s cold, windy winters.

The dining commons will house what may be the entire community’s most remarkable achievement: the first full commercial kitchen in a Living Building project. Kitchens have been something of a Holy Grail for the LBC. Their intensive demands for energy and water, as well as complex appliances that might not qualify as free of toxic Red List chemicals, have caused buildings with kitchens to shy away from the LBC, and LBC projects to shy away from kitchens.

“This isn’t going to be a reheating kitchen,” Thompson notes. Most often, cooks will prepare fresh produce directly from farm for tables seating up to 150 people. “When you’re making things from scratch you can’t hide the embodied carbon in processed foods.”

The team hired Advanced Foodservice Solutions, a Pennsylvania company that has previously consulted on all-electric kitchens. The design calls for convection ovens and induction cooktops. But the dishwasher turned out to be the biggest challenge. Heating the dishwasher’s water will alone demand more electric power than the entire dorm building. Energy modeling showed the school had to expand its solar energy capacity to accommodate just that appliance.

As construction moved through the winter, the project achieved another couple of firsts. The Ecology School’s master plan became the first ever approved for a Living Community project. And because construction was already underway, ILFI also informed Dumsch that the campus had now attained “Emerging Community” status. The little school had effectively leapfrogged more established LCC projects being shepherded by much larger organizations.

That news arrived in March, just as the coronavirus pandemic had begun to ravage New England. Although Maine’s governor quickly implemented a general lockdown, it was hit a bit less restrictive than those in other, more hard-hit states in the northeast, and the school’s construction team was relatively lucky. Concrete pours, framing and other outdoor work was allowed to continue. By the time the subcontractors began to move indoors, the restrictions were being eased.

Fortuitously, supply-chain issues that hit other construction projects weren’t severe at The Ecology School. Dumsch and Thompson credit the LBC’s emphasis on locally sourced products and materials. Hancock Lumber, a family-owned company based in Maine, fabricated wall sections and trusses from pine and spruce grown in Maine and Quebec and certified by the Forest Stewardship Council. Zachau Construction, the general contractor, sourced FSC-certified white-pine siding from Maine, through Hancock as well.

“We’re not waiting on stuff to come from California or China,” Dumsch notes. So far, at least.

The project has had its challenges, of course. To finance most of the $14.1 million budget (for both real estate and construction), the school tapped into government loans — the bulk of which came through a U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development program. But loan payments require cash flow, and revenue has been in short supply since the school suspended programs since March. Closing a $3.6 million gap in funding that isn’t being providing by the loans hasn’t been easy in the midst of a pandemic for a nonprofit that had never before engaged in a major capital campaign.

“It has been a very steep learning curve,” says Board Chair Mary Martin, a retired school principal. “We’ve got a lot of irons in the fire, and we’ve just kind of worked through them.”

Still, the Living Buildings are on track to be completed in the fall. In June, another bit of good news arrived: Maine-based Poland Spring Water , a longtime supporter of the school, announced a $500,000 grant to the capital fund.

As is his wont, Dumsch is looking toward the uncertain future opportunistically. He’s already making a case for the Ecology School to serve as a model of COVID-19 resilience. For one thing, he expects the campus’ reliance on its own energy, water and food to make the school more economically resilient. For another, he anticipates expanded programs to accommodate an increase in interest any place that can help people learn to live in better balance with nature.

“We were founded on an aspirational model,” he says. ““There is going to be a post-pandemic. Places like The Ecology School are going to have a really important place in the healing and the education moving forward.”