Who knew that Google Glass would flop? Or that ceiling fans would enjoy a high-tech comeback? The best view of innovation often comes through the rear-view mirror.

It’s anyone’s guess where electrochemically activated disinfectants will fall on the oblivion-to-success spectrum. But a handful of entrepreneurs and established companies are hoping that janitorial crews will latch onto ECA technology as a non-toxic approach to killing pathogens. With coronavirus now a top concern, ECA products — also known by their active ingredient, hypochlorous acid — could be positioned to upend the $1.4 billion surface-disinfectant industry.

“It’s very green in the sense that the only input is table salt. And the output has a lot of good biocidal qualities but is the least toxic disinfectant you can find on the market place,” said Hungnan Lo, vice president for technical operations at Innovacyn, a longtime leader in ECA products.

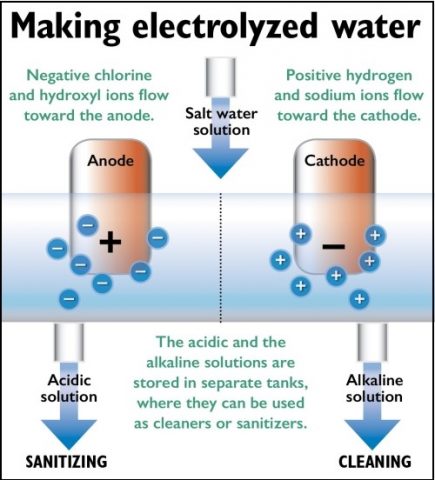

The technology has been around for decades. Electrochemical activation relies on a simple reactor, or generator, that uses an electric current to scramble and reorder molecules of water and salt. That process produces two new liquids that happen to be useful for cleaning and hygiene: sodium hydroxide (better known as lye), which is a detergent, and hypochlorous acid, which is a powerful disinfectant.

Hypochlorous acid sounds almost too good to be true. On one hand, it’s less toxic to mammals than the active ingredients of many conventional, environmentally friendly disinfectants. It’s rated at the lowest level (Category IV) on the Environmental Protection Agency’s acute toxicity scale.

On the other hand, hypochlorous acid is lethal to microscopic bacteria, viruses and fungi. By some criteria, it kills pathogens more quickly than chlorine bleach.

From industrial to commercial uses

Surface disinfectants currently aren’t the main focus for most major players in the field. Klarion, a startup that was purchased by nozzle-making giant Spraying Systems Inc., makes large ECA assemblies consisting of tanks, tubing and the generator. It markets them primarily as general sanitizers in dairies, hatcheries and other food processing plants.

According to a company salesperson, Klarion’s smallest units are appropriate for use in disinfecting large commercial buildings. But the fees set a high entry point: Leases start at $400 a month.

Companies are addressing the price-point problem by offering one of two types of scaled-down products. Among them is Envirocleanse, a Texas-based startup owned by a subsidiary of Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway. Last year, Environcleanse released a bottled hypochlorous acid disinfectant. It’s one in a handful of hypochlorous acid products that has made it onto the EPA’s “List N” of surface disinfectants appropriate for use against SARS-CoV-2.

Lo says Innovacyn, which is based in California, is working on a bottled product, as well. The company already uses ECA to manufacture hypochlorous wound-care gels and solutions for people, pets and livestock. But, he notes, the primary challenge for off-the-shelf hypochlorous acid products is that the chemical’s molecules are weakly bound together, causing the disinfecting power to dissipate within a couple of weeks. Put plainly, they have a short shelf life.

“There are formulations to try to extend the shelf life,” Lo said. ”That’s where all the trade secrets and know-hows reside.”

Do-it-yourself electrolyzed water

Other ECA companies are taking a very different tack. They’re marketing miniature devices. Water, salt and, in at least one case, vinegar, are added into an appliance that looks something like an electric tea kettle. That’s where the chemical reaction takes place. At that point, either the liquid — a combination of the cleaner and disinfectant — is poured from the reactor unit into a spray bottle, or the flask is detached from the generator and becomes a spray bottle.

Such units are being marketed to households, offices, shops and schools. Like many new technologies, they’ve spawned a sort of marketing wild west. For consumers, it’s difficult to tell which products are reputable — an important consideration when you need to kill deadly pathogens. And unlike conventional disinfectants, the reactor assemblies are appliances: Because the disinfectant is produced in the field, it’s difficult to evaluate its potency.

RELATED STORY

COVID-19 in the office: A Guide to Guides

Only one small device maker has managed to make the EPA’s List N and also has gone through the process of becoming Green Seal certified. For quality control, that company, Force of Nature, supplies its users with capsules that calibrate the amount of salt and vinegar that is added to the water. (Vinegar is added to stabilize the balance of sodium hydroxide and hypochlorous acid in the vessel.)

The Force of Nature “Starter Kit” currently costs $56 — a lot more than the $6 price of a 22-ounce spray bottle of Lysol Multi-Purpose Cleaner With Hydrogen Peroxide (another environmentally friendly disinfectant). But Force of Nature Chief Marketing Officer Melissa Lush notes that the device can be used over and over again, so over time it could cost dramatically less.

Force of Nature offers a peek at what could be one entrepreneurial future for ECA. Since the 1990s, the industry has been dominated by companies, typically founded by engineers or scientists, that focused on highly specialized industrial applications.

Neither Lush nor CEO Sandy Posa have scientific backgrounds. They’re both veterans of household consumer giant Procter & Gamble. They founded Force of Nature six years ago, leading with the idea that they were creating a “brand” to serve a broader consumer market.

Posa came across the electrolyzed water when he “was looking for technologies that could go after unmet consumer needs,” Lush wrote in an email.

“He noticed that it was only used in the industrial space and thought it would make a ton of sense in the consumer space, too,” she continued. “I had worked with him at P&G doing new product development, so I jumped in to help figure out how to commercialize it because it has a lot of different potential applications.”

They brought on a chief technology officer to engineer the product and eventually a couple more support staff members. Like similar consumer-brand startups, however, Force of Nature outsources manufacturing and distribution. It contracted a factory in Mexico. The products are packaged and shipped from a Buffalo, N.Y., distribution center.

One can easily imagine the company or a competitor following a familiar path for innovative products: proving its popularity and growing to the point that it’s sold to a large established company. With the dramatic increase in demand for surface disinfectants, coronavirus may have put acceptance of ECA products on a fast track .

“We have scaled up our production by 10X to meet demand,” Lush wrote. “The need for disinfectants has gone up dramatically.”