Southern forests are among the most productive on Earth. Covering just 2 percent of all the earth’s forestlands, they produce 18 percent of its pulpwood. No wonder they’ve been called the world’s “wood basket.”

With a mass timber structure composed of glue-laminated and nail-laminated timbers, the Kendeda Building has a direct connection to Southern forests. Of course, the extensive amount of salvaged wood in the building also came from regional forests, albeit prior to earlier uses. Given these connections, and the project goal of promoting regenerative design and construction, we explore the state of Southern forests in the post that follows.

With a mass timber structure composed of glue-laminated and nail-laminated timbers, the Kendeda Building has a direct connection to Southern forests. Of course, the extensive amount of salvaged wood in the building also came from regional forests, albeit prior to earlier uses. Given these connections, and the project goal of promoting regenerative design and construction, we explore the state of Southern forests in the post that follows.

In addition to being highly productive, Southern forests also are the center of biodiversity in North America. More than 3,000 species of plants, 595 avian species, 246 mammals, 170 amphibians and 197 reptiles make their homes in Southern forests.

Whatever you value – water, carbon storage, biodiversity, wood and pulp, jobs and economic development, or recreation – Southern forests deliver. Yet with so much demand, it’s no surprise these forests are under pressure from suburban development, agricultural expansion, forestry and a changing climate.

So, what is the state of Southern forests?

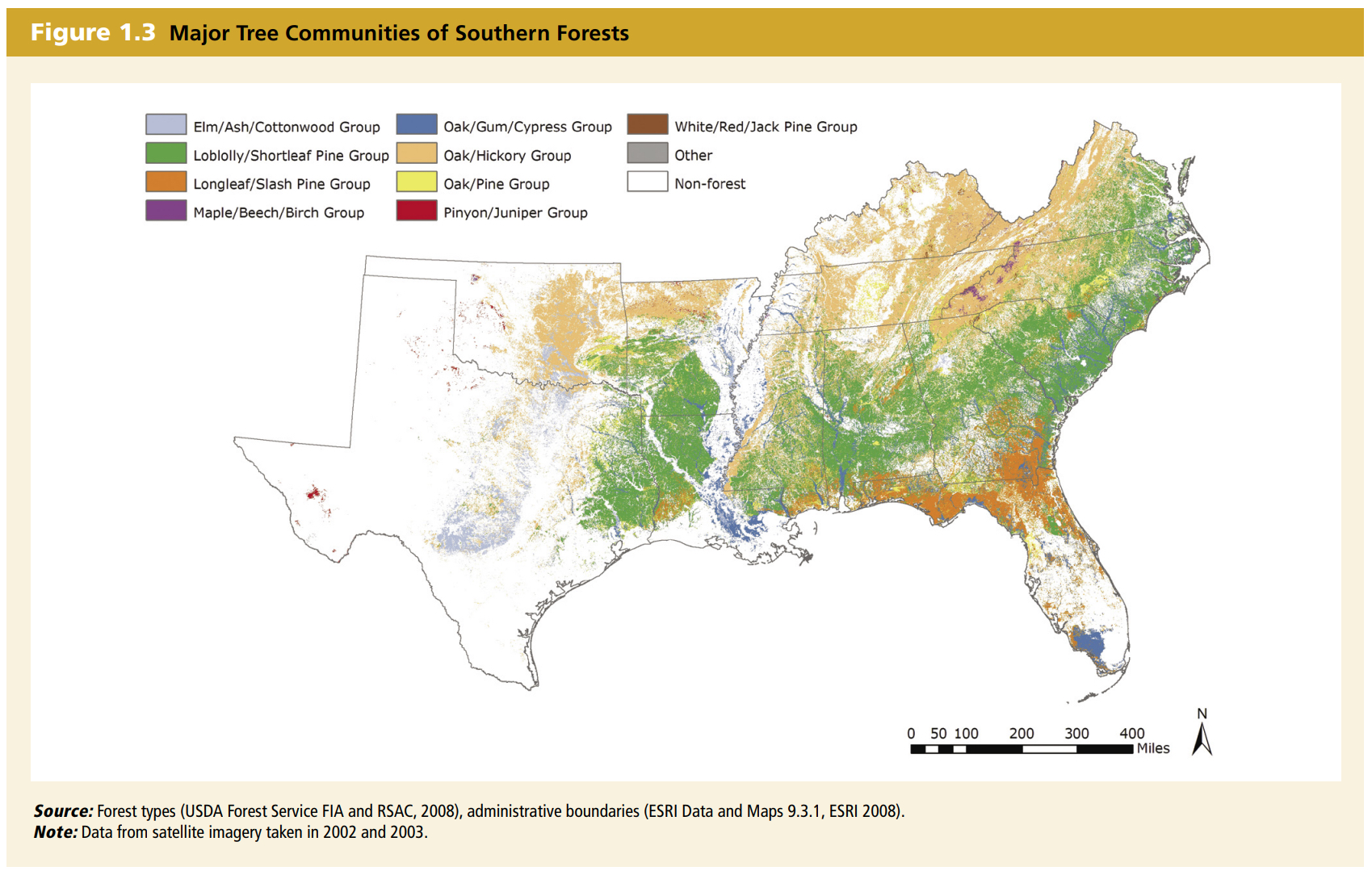

This is a big question for a huge, diverse region that extends from the hardwood stands of the Appalachian Mountains to bottomlands along the Gulf Coast. Covering 214 million acres, forests represent 40 percent of the land area in the 13 southern states ranging from Oklahoma to Florida to Virginia.

There are, however, a few overarching trends.

When the World Resources Institute released the landmark report, “Southern Forests for the Future” in 2010, it projected that 19 million acres of Southern forest would be lost to suburban development from 2020 to 2040. Since Europeans began settling the South in the 1600s, more than 99 percent of the original forest area has been harvested at one time or another. Much of that area is now second or third generation forest. Even so, 40 percent of the original forested area has been lost since European settlement began, sometimes at significant ecological cost, according to the report.

Because 86 percent of Southern forests are privately owned, with two-thirds held by individuals or families rather than corporations, economic pressure can lead to forest loss, especially when family forests are passed from one generation to the next. The average size of a family forest in the region is just 29 acres, which makes consistent management across a large landscape tricky. Nonetheless, private Southern forestlands are actively managed. Collectively this landowner category represents 58 percent of all timber harvested in the United States.

The most common forest types in the region include oak/hickory (84 million acres), loblolly/shortleaf pine (55 million acres), oak/pine (24 million acres), and oak/gum/cypress (21 million acres), which collectively comprise 86 percent of Southern forest area. When it comes to tree farms, loblolly and shortleaf pine are kings, covering 71 percent of the South’s planted forest area.

Yet the focus on a couple of high-value species can come at a cost to diversity. Longleaf pine, which once carpeted as much as 92 million acres of the region, today covers just 4.3 million acres, primarily in Florida, Alabama, Georgia and the Carolinas. While the transition to monocultural plantations played a role in the decline in longleaf pine, wildfire suppression was also significant. Longleaf pine is fire resistant, and as wildfire was suppressed over the past century, other species moved in and crowded it out. Conservation groups are actively working to restore longleaf pine forests, which serve as the primary habitat for red-cockaded woodpeckers and many other wildlife species.

More broadly, widespread “high grading” over the past 100 years has degraded Southern forests. Simply put, high grading focuses on harvesting the biggest, most valuable trees, which typically deliver the highest price in the market. Repeated selection of these trees eventually reduces the overall health and quality of the remaining forest, both economically and ecologically.

Experts mince no words in criticizing this still-common practice. As four foresters put it in Southern Forest Science: Past, Present, and Future, “This form of timber harvesting, commonly known as selective harvesting, is in reality high-grading, a practice that should be condemned by foresters. This degenerative practice is not to be confused with the silviculturally sound selection system, in which the desired tree species mix of all size classes is maintained.”

Climate change and population growth are bound to put additional pressure on Southern forests. For example, the area burned by wildfires in the region is projected to rise by 4 percent annually due to climate change and changes in land use. With many pulp and lumber mills closing and increasing management pressure on Southern forests, the story varies by location. While forest area across the region is relatively stable, with 1 to 2 percent of the area moving into or out of forest cover each year, Georgia leads among tree-cover loss, especially in the fast-growing suburbs around Atlanta, with 7.5 million acres lost since 2000.

Regeneration and restoration is possible, however, and it need not place the interests of owners and environmentalists in conflict. Across the region, many owners are working to improve the health of their family forests. Some are motivated by a conservation ethic. Others benefit from government incentives, such as those offered by North Carolina’s Present Use Value Program, which defers tax burdens if forests are managed sustainably. By lowering the costs of managing a forest, the North Carolina program decreases pressure to deliver the highest value trees to the market.

Given the prominence of privately owned forests, there is an opportunity for the wide array of public incentive programs and the markets themselves to play a role in regenerating and restoring them.

It isn’t clear that such innovative programs will do enough to arrest the loss of Southern forests. They certainly could help. What is even more certain, however, is that the stakes are high: From many perspectives, Southern forests are a globally significant resource that deserves preservation.

Brad Kahn is communications consultant based in Seattle, Washington. His practice focuses on climate, forests and green building, with clients including the Forest Stewardship Council, David and Lucile Packard Foundation, International Living Future Institute, and Kendeda Fund. He has a Master’s degree in watershed systems and management from the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.