Late last month, I caught three Skanska pre-construction engineers on the cusp of innovation. They were crouched toward the floor in a warehouse on the edge of the Georgia Tech campus, nailing two-by-fours to two-by-sixes.

OK. So, they weren’t installing a rooftop apiary or a state-of-the-art direct outside air system. But a year-and-a-half into design and a couple of weeks after the official construction launch of the Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design at Georgia Tech, this may have marked the first time power tools actually were engaged on the $25 million project.

Work at the building site will ramp up slowly before beginning in earnest this winter. Meanwhile, in one small space for 45 minutes, three white-collar guys from a global construction giant were bringing together issues related to the Living Building Challenge’s Energy, Equity and Materials petals —all with the power of a nail gun. Last month’s little test provided an example of the intricate steps involved in planning out construction of a Living Building, as well as the way small decisions can drive multiple goals forward by just a step or two.

The task looked more straightforward than all that. The three men — Skanska Director of Project Solutions Jimmy Mitchell, Vice President for Preconstruction Bob Kovacs, Senior VP for Preconstruction Kayle Gastley — were timing how long it would take three or four workers to assemble the building’s uniquely designed wooden floor decks.

Nowadays, structural floors in commercial buildings typically are composed of concrete poured over a rebar grid sitting on an elevated metal pan. But the sustainable properties of wood are tilting many applications away from concrete and steel in the greenest of buildings.

“We wanted to use wood for two primary reasons,” Lord Aeck Sargent architect Joshua Gassman explained in a separate interview. “One is that there’s a lower amount embodied energy and embodied carbon in wood than in concrete — by a huge amount. And second is just for the beauty of it. It’s a natural material and provides a distinctive warm, natural look.”

I reminded Gassman of another benefit: Raw wood is basic. It’s not manufactured from other products or composite materials. It doesn’t require a complicated chain-of-custody investigation to figure out where various components were sourced and what went into each of those components. And lumber isn’t likely to contain any of the toxic chemicals that could harm the people who manufacture the product, install it or occupy the building.

“Part of the materials strategy is about putting the least-processed products in the most places we can,” Gassman noted. “It’s just like when you’re buying some ice cream: You don’t want to look at the label and see a lot of ingredients that you can’t pronounce. You just want it to be made of milk, sugar, eggs and whatever flavor is supposed to be in there.”

Gassman is project manager for the Kendeda Building design team. As best he recalls, it was a fellow architect, Brian Court, who brought up the idea of nail-laminated floor decks. That makes sense because Court — a partner at Miller Hull in Seattle who is working with Gassman as the building’s lead designer — also was lead designer at the Bullitt Center, which probably is the world’s best-known Living Building. The Bullitt Center used similar screw-laminated floor panels.

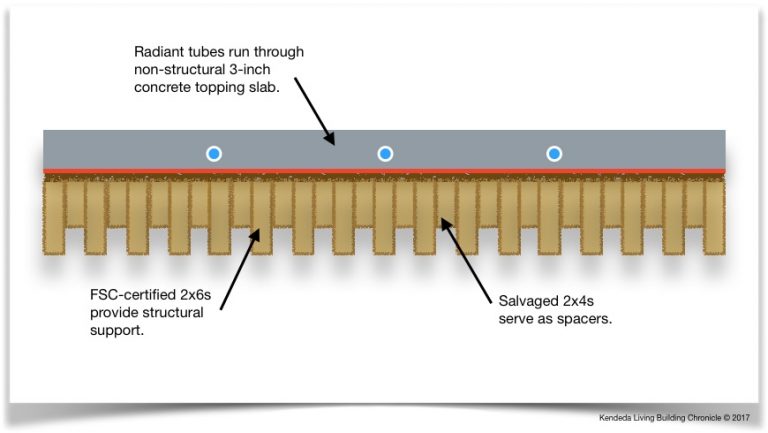

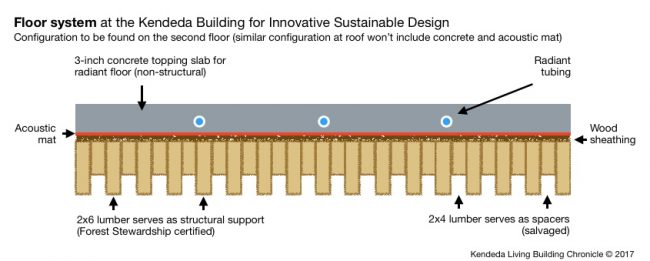

Members of the Kendeda design team think they’ve found a way to improve upon the Bullitt Center’s approach. The decks in the Seattle building are composed of two-by-sixes turned on edge. As the building rose to six stories, workers nailed the boards together in place.

Late last year, Gassman ran the design concept by Uzon+Case, structural engineers on the Kendeda Building.

“They said that was fine, but they also told me that every other two-by-six wasn’t even necessary,” Gassman said. In other words, only half the two-by-sixes are needed to hold up the weight of the entire floor system. The ones in between are really spacers. They also help to create an even, unbroken surface on the topside of the structural floor.

So Gassman, with the help of Skanska’s Mitchell, came up with a scheme that had several advantages. Rather than just nail two-by-sixes to together, they decided to alternate the two-by-sixes with two-by-fours.

As architects, Gassman and Court liked that idea, because the exposed underside of the panels would create an “articulated” pattern on the ceiling — more attractive than just a flat ceiling and less likely to show imperfections.

As a contractor with a passion for reusing materials, Mitchell loved the idea, because it’s a lot easier to find salvaged two-by-fours than two-by-sixes. Now, he had to figure out where to source both dimensions of lumber.

The Living Building Challenge requires wood used in projects either to be certified by the Forest Stewardship Council or to be salvaged. For two reasons, Mitchell already knew that the two-by-sixes would need to be FSC certified. First, as structural components, they must be tested for strength — something that would be costly and time consuming to do for salvaged lumber. Second, it’s a lot more difficult to find salvaged two-by-sixes than it is to find salvaged two-by-fours.

Because the floor’s structural integrity won’t rely on the spacers, however, the two-by-fours can be salvaged. And it happens that Mitchell is intimately familiar with an organization well placed to create a supply chain for salvaged two-by-fours in Atlanta. Five years ago, he was founding board member for the Lifecycle Building Center, a nonprofit in Atlanta’s West End dedicated to salvaging and repurposing used and surplus building materials.

So Mitchell alerted the center to be on the lookout for two-by-fours. Staff there quickly settled on a nifty source: Atlanta area film sets. Since last spring, they’ve been asking film production companies across the metro area for their used two-by-fours, and reserving them for use in the Kendeda Building. So far, Mitchell says, they’re up to a couple of thousands pieces.

“They’re perfect for what we need,” Mitchell said, “because they’ve only been used for a few months, maybe less. So, they’re not dirty, and they’re not going to have insect damage.”

In addition to sourcing materials during the pre-construction phase, Mitchell has to figure out how to actually put together unconventional components. So he called the contractor on the Bullitt Center to find out how workers there constructed the floor decks.

It turns out that the Bullitt Center was required to build its decks entirely of two-by-sixes because, as a six-story structure, the Seattle building had to meet the more stringent fire code for high-rises. In other words, the Bullitt Center couldn’t have adopted the mix of two-by-fours and two-by-sixes that the Kendeda Building design team has settled upon.

Mitchell’s contact offered a bit of practical advice from his own experience: Rather than putting the boards together in place, he said, workers could have saved time and effort by nailing them into units at ground level and then installing the units.

That gave Mitchell the idea for his own production scheme. Skanska will either hire workers directly or hire a subcontractor to assemble the panels in a warehouse that Georgia Tech is allowing the contractor to use to store salvaged materials for the Kendeda Building. Then, they’ll truck the prefabricated units to the construction site a mile-and-a-half away.

That gave Mitchell the idea for his own production scheme. Skanska will either hire workers directly or hire a subcontractor to assemble the panels in a warehouse that Georgia Tech is allowing the contractor to use to store salvaged materials for the Kendeda Building. Then, they’ll truck the prefabricated units to the construction site a mile-and-a-half away.

Now, Mitchell had another problem to solve: How much time and money should Skanska set aside to assemble the panels? Even in a warehouse, nailing more than 20,000 boards into six-foot-wide by 12-foot-long panels will take time. It’s likely to be a lot more labor intensive than pumping concrete.

That’s what brought him, Kovacs and Gastley out to the warehouse on a warm November morning. Their task: Time how long it would take to assemble one five-foot-wide, 12-foot-long floor deck. Four people probably will be involved when it comes to working on the floor decks that actually will be used in the building, and the workers won’t have to bend down because the assembly will probably take place on a table-height platform. But the test still required less time than they expected — just over 43 minutes. All told, Mitchell figures, it would take three full time workers and a supervisor about two months to assemble the 470 panels needed for the building.

The labor-intensive task could create an opportunity to meet another of the Kendeda Building’s goals. The Living Building Challenge’s Equity Petal encourages projects “to foster a true, inclusive sense of community that is just and equitable.” Georgia Tech officials have made clear that they want the Kendeda Building to serve as a model for that ambition. And, last summer, the Equity Petal Work Group assembled to push the project’s equity goals identified one of those goals as providing career-building opportunities for residents in the struggling neighborhoods just to the west of the campus. What if nailing together lumber provided an entry point for potential careers in construction for some west side residents? It would be a small step toward some very ambitious, larger goals, and it’s not clear yet whether practical concerns that always crop up in construction projects might get in the way.

But Mitchell already has been in discussions with a nonprofit organization called Westside Works dedicated to job training of west-side residents and to matching them to jobs. The stringent requirements of a unique project, he admits, can force builders to find solutions that otherwise might never be explored.

“You’ve got to be open to doing things differently,” he said, as he, Kovacs and Gastley admired their work. “We’ve been seeking bids on this part of the job, but we honestly didn’t know how much time it would take, so we had no way of knowing what amount was reasonable. Now we know.”