When students return to the Georgia Tech campus this fall, they’ll find opportunities to participate in six pilot projects intended to improve the design, construction, operation and evaluation of sustainable buildings.

Each of the projects is tied to the Living Building at Georgia Tech (and is funded in part through the Kendeda Fund gift that’s paying for the building). But the real focus of the pilots is longterm: to leverage both the Living Building at Tech and the university’s academic firepower by developing tools and processes that can improve buildings.

“I’m convinced that these projects and others like them will end up seeding larger grants,” says Architecture Professor Michael Gamble, who chairs the Living Building Academic Council. “You’ll start to see the words ‘Living Building’ show up in applicants because it encompasses a lot of the kinds of ideas that people will be interested in funding.”

The Academic Council selected the six pilot projects from among 22 proposals. Each received a grant of $10,000. They’re part of the “leverage” effort that Kendeda and Georgia Tech are pursuing to broaden the building’s impact on construction, especially in the Southeast. More grant-giving rounds are expected in 2018 and 2019, according to Drew Cutright, who manages the Living Building’s leverage activities.

Here’s a quick look at this year’s recipients:

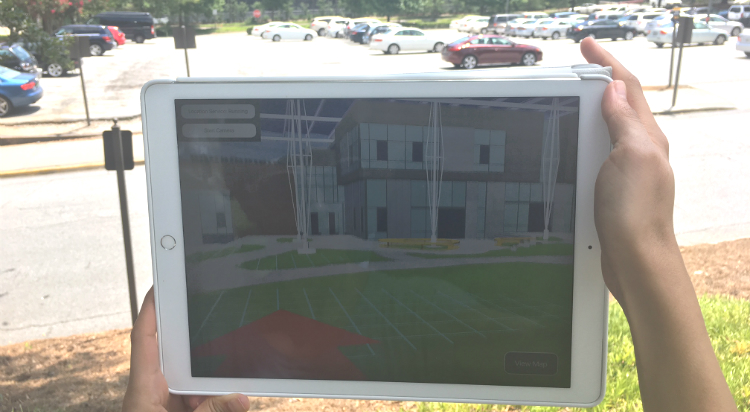

Crowdsourcing a building via augmented reality

Occupants typically don’t have much say about a building’s design until after it’s built. Then, it’s too late. The “Living Building Community Crowdsourcing” pilot project aims to give future occupants, along with other stakeholders, a chance at making meaningful suggestions beforehand.

Civil Engineering Professor John E. Taylor’s is working with Alissa Kingsley, one of the building’s architects, to develop an interactive, augmented-reality model of the building. The pilot project will allow potential occupants and visitors to “spatially visualize” the building by taking a 3-D tour via an iPad.

This technology has the potential to allow visitors to view and experience the building from several perspectives, gather direct feedback from users that captures their insights on arbitrary elements, and deliver diverse community ideas to inform building design decisions in a more equitable manner.

Part of the project will involve student canvasser, at the building itself, gathering feedback by engaging passersby to interact with the augmented reality program. While many design decisions already have been made, the feedback could influence interior and exterior details. The feedback will be structured to address the Living Building Challenge’s seven petals.

Signage will be posted at the deployment site and across campus to promote engagement from all students, staff, and visitors. After the deployment, collected data will be analyzed and summarized to facilitate its incorporation into the building design.

Taylor and Kingsley, who are members of Georgia Tech’s Equity Petal Working Group, view crowdsourcing as an opportunity to gather information from a diverse set of potential occupants “while reducing the risk of costly fixes in the future.” They argue in their project description that grassroots feedback “is a departure from a top-down approach, in which building designers may be disconnected from a project’s end users.”

Taylor is leveraging a virtual reality platform developed at the university’s Network Dynamics Lab under a National Science Foundation grant. He hopes it will lead to further development of crowdsourcing applications for the built environment. His team currently is developing an extended version of the application that models the entire campus to crowdsource feedback on each of the seven Living Building Petals on how Georgia Tech could evolve to a “Living Campus.”

Continuation of this feedback loop could be deployed during the construction and operations phases of the building to sustain connections between occupants and the building and show Georgia Tech’s commitment towards creating inclusive spaces. Findings from the data will likely be broad, and be able to be applied across other buildings on campus or inform design standards.

This fall, Taylor plans to involve an interdisciplinary civil engineering course he teaches on Smart and Sustainable Cities in testing and development of the augmented reality app.

Organizing data on sustainable materials

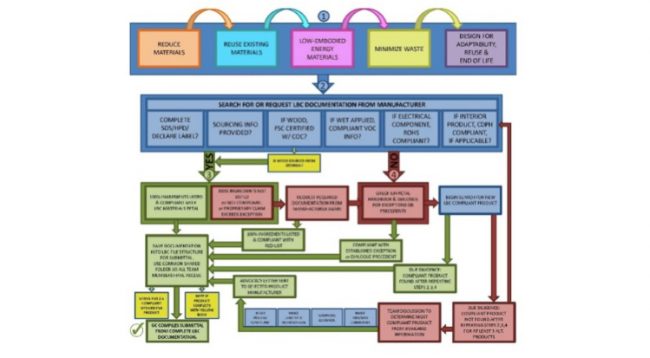

One of the Living Building Challenge’s most difficult requirements is that it bars materials containing “Red List” chemicals from being used in the building.

LBC’s “Red List Imperative” and other parts of the Materials Petal force architects, engineers and contractors to spend loads of time researching the materials and products being considered for the building. It’s part of a broader, and growing, issue involving materials research and transparency.

The AEC (Architecture, Engineering, Construction) industry has not organized itself in any meaningful way to address this challenge, because the data that describes building material constituents and production processes are non-existent, held to be proprietary and thus not reported, or are provided without a consistent structure.

Building information management techniques may hold the key to addressing this challenge. The Georgia tech Digital Building Lab is one of the leading research institutions in Building Information Modeling, or BIM. It uses intelligent 3D models tagged with information and connecting to distributed databases of project information to integrate complex design and construction projects. Digital Building Lab Director and Architecture Professor Dennis Shelden, who’s overseeing the pilot project along with Adjunct Professor Russell Gentry, write in an that “graduate students are working with personnel at Skanska USA to develop ways of categorizing and tracking materials that are being incorporated into the building systems, for the purposes of identifying, visualizing and reporting on Red List and other environmental performance aspects of the project.”

According to the project description.

The LBC provides us with a unique opportunity to leverage [building information modeling] data management processes in conjunction with other data systems including materials databases, sensors and construction management tools to create a best-in-class example of the potential for low environmental impact building construction and operations.

Tracking biodiversity at the Living Building site

Biology Professors Marc Weissburg and Emily Weigel will lead students in a core ecology course as they pore over plants and animals on the Living Building site, both before and after construction.

Data will be collected as part of a class project and will be ongoing in order to document long term patterns of growth and development of the surrounding community (succession). The educational activity will use the LB to discuss how the built environment can impact biodiversity and ecosystem function, and use the LB as a case study.

Their project is building on the idea that the Living Building project team and, later, its occupants must truly understand the surrounding environment in order to protect and even augment it.

We will develop an inquiry-based, multi-week laboratory unit to examine how biodiversity is affected by the Living Building. The module will focus on urban ecology to cover fundamental concepts in ecology, how the urban environment affects ecological processes, and the specific strategies that can be employed to ameliorate these potentially harmful effects to yield more resilient and sustainable human infrastructure. Comparisons to other campus or local urban areas will facilitate identifying the specific impacts of the Living Building. Products will include a short video on these subjects suitable for lay audiences and students from middle school to beginning undergraduates that will feature the work done by the Ecology Lab to document the effects of the Living Building.

Weissberg and Weigel, who alternate teaching the ecology course, plan to incorporate their study of the site into the curriculum on an ongoing basis.

Living Building Equity Champions

Ambitious work on Georgia Tech’s Equity Petal will get a boost from five to 10 students who’ll serve as the “Living Building Equity Champions.”

Under the auspices of Keona Lewis, Atira Rochester and the Center for Student Diversity and Inclusion, the students are expected to:

• engage and expose underrepresented students “to the relevance and importance of equity within sustainability,”offer input in the building’s “design and development,”

• organize activities, speakers and other events, and

• help to open Living Building access “to the greater Atlanta community, particularly K-12 students.”

The Champions also are expected to help identify equity-related programs and initiatives that could be housed in The Living Building after it’s completed. Among them: “establishing an equity resource center, creating an equity visitors guide for The Living Building, profiling underrepresented leaders in equity and sustainability, utilizing sustainable foods for meals from diverse backgrounds, and exploring professional development opportunities that align with sustainability efforts.” Many of those ideas grew out of the Equity Petal Work Group, led by Georgia Tech’s Drew Cutright and Jennifer Hirsch.

The project also has a research component. The plan is to use surveys, interviews and other data to evaluate both the interplay between sustainable building, sustainable education and under-represented groups, and the impact of the pilot project’s own work.

“Living” dashboard

Eight Sustainable Undergraduate Research Fellows, aka “SURFers,” will develop an interactive dashboard that will monitor and display energy, water and other aspects of the Living Building. Researchers Michael Chang and Dana Hartley envision a prototype that frames the information “through each of the seven Living Building petals.” But they also expect the system to be able to expand “outward through the scales of the campus, the city, the region, and the globe.”

The modeling and simulation software they’re using is described as “a user-friendly interface [that] enables expert and lay people alike to ‘play with the knobs and dials’ to change settings and explore consequences across multiple connected, complex systems (e.g. water, energy, and health).”

Chang and Hartley hope the pilot will serve as the first phase of a longer-term “vertically integrated project” in which students are always involved in the Living Building’s use and performance – past, present, and future. In an email exchange, they write:

Most building dashboards lose their novelty soon after building commissioning and become stale, obsolete, or inoperable within a few months of their debut. In contrast, this living monitoring system will adapt as the building moves through its lifecycle, as its occupants transition through, and as the climate and environment in which it resides evolves. Students in the future may have very different interests and needs than students today. They will benefit from the efforts of those that came before them, but so too will they be able to bend the monitoring system – and hence the building also – to their contemporary interests.

Middle school lesson plans for biologically inspired design

Georgia Tech’s Center for Education Integrating Science, Mathematics and Computing already holds a large National Science Foundation grant to “develop, deploy and test a three-year engineering sequence for Georgia middle school students.”

Science Education Program Director Sabrina Grossman and Research Scientist Michael E. Helms say the pilot project leverages that grant by developing lesson plans that focus on the emerging field of biologically inspired design.

Science and technology lesson plans have an equity component because they’re particularly helpful to schools with fewer resources, Grossman and Helms note. They plan to target schools with a high population of less-advantaged children, particularly in rural areas. According to their pilot description:

Using the LBC as a living laboratory, we will identify sustainable building challenges faced by the LBC and available supporting documentation (video footage, design documents, building plans, data generated by the building, expert interviews, etc.) We will also analyze student projects and materials collected from [courses] at Georgia Tech that focused on sustainable building challenges. With our [Center for Biologically Inspired Design] partners, we will translate these materials into suitable middle school biologically inspired design challenges.

The “challenges” will be tailored to subjects taught statewide to students in each grade: Sixth graders will focus on water issues as part of their earth science course. Seventh graders will focus on natural materials as part of the life science. Eighth graders will focus on thermoregulation and energy in physical science.

Helms and Grossman already have engaged a middle school science teacher and a Georgia Tech undergrad to gather documentation of the building.

This pilot will disseminate actionable lesson plans and student materials using the LBC as the centerpiece for a multi-year STEM learning experience, targeted at low income and underrepresented youth throughout Georgia (equity petal). This includes distant rural populations that may otherwise not have access to, or even knowledge of, this one-of-a-kind building in the Southeast. This pilot immediately extends the reach of the LBC to as many as 100 teachers, many in rural schools or serving underrepresented populations.