In his book, “Architecture and Ritual: How Buildings Shape Society”, the late architectural historian Peter Blundell Jones explores a hypothesis that architecture and ritual are closely related. He posits that the interaction between people and their habitat is much more complex than “form follows function.” In attempting to define architecture after challenging existing definitions, he points to the narrowness that results from relying purely on material and technical points of view. A more meaningful definition, he argues, would also include the social, spiritual, and cultural aspects.

The Living Building Challenge certification, in its own way, explores a more complete definition of architecture. While acknowledging their importance, it transcends the material and technical aspects, and compiles the issues it considers relevant into an all-or-nothing framework. Consider this statement from the introductory text of the standard’s guidance document:

During a March 2017 presentation at Georgia Tech, LBC’s founder and chairman of the board of the International Living Future Institute, Jason F. McLennan, focused on similar themes. For projects not pursuing the LBC certification, he encouraged the design teams to ask themselves, at a minimum, the following three questions related to ‘Regenerative Design Practice’:

- Does our design create more abundant conditions for life and the diversity of life? (Ecotone question)

- Does our design honor the spirit and potential of this place? (Biophilia question)

- What would other species do to inform this design? (Biomimicry question)

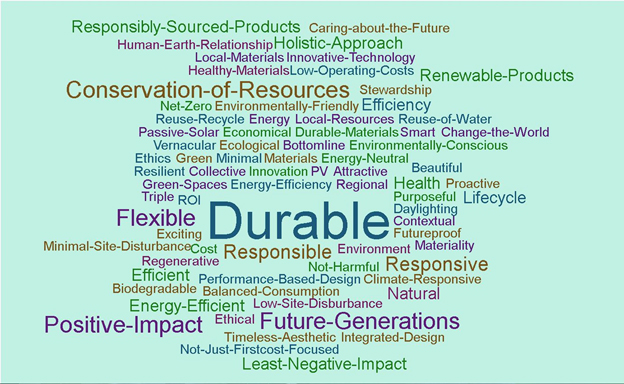

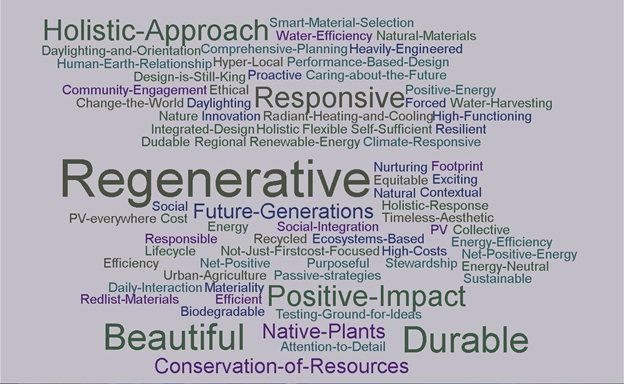

In February 2017, Lord Aeck Sargent conducted an interesting compare-and-contrast thought experiment. At an internal, firm-wide presentation on the progress of the Living Building at Georgia Tech, attending staff were asked to list three ideas that demonstrated what sustainable design meant to them before the presentation. They were asked to perform the same task after the presentation. We wanted to determine if discussing and exploring LBC ideas would have an impact on their responses. Of the 40 or so responses, 58 percent of the “after” responses differed from their corresponding ‘before’ responses. Here is a summary of the findings:

- The term regenerative occurred once in the before responses and six times in the after responses.

- The term beautiful occurred once in the before responses but four times in the after responses.

- The term durable (or variants) occurred 12 times in the before responses but only four times in the after responses.

As LAS has undertaken its latest sustainability strategic planning effort for 2017, in concert with a firm-wide dialogue to establish Core Design Values of responsive design, the term ‘regenerative’ has figured prominently in the discourse.

Consistent with Jason’s admonition to consider regenerative design for all projects, we are attempting to establish minimum sustainable design criteria, improved design team resources, and enhanced accountability for the routine incorporation of sustainability considerations, not just for ‘deep green’ demonstration projects that have sustainability as a key program driver, but for all design efforts undertaken at LAS.

This article is reprinted with permission from the Lord Aeck Sargent blog. Ramana Koti (BEMP, LEED AP BD+C) and Jim Nicolow (AIA, LEED Fellow) were lead authors. Joshua Gassman (RA, LEED AP BD+C), Alissa Kingsley (LEED AP) and Whitney Ashley contributed to the post. All are with LAS.