Upon completion of the Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design, we asked seven team members to reflect on their work on a complex Living Building Challenge project. As a lens, they used the LBC’s seven Petals. Check out all the Petal Columns by clicking here.

The Materials Petal has a formidable reputation in Living Building Challenge circles.

The LBC’s Energy and Water Petals set high bars. But they, at least, can be addressed with engineering solutions that usually are modeled and decided upon during the design phase.

The materials that go into a complex construction project present more of a many-sided, ongoing conundrum. Building products, and the ingredients they contain, are manufactured by an evolving global industry. Complex supply chains, tens of thousands of companies, millions of employees, and countless intricate, industry-specific considerations all play a role.

Amid this complexity, each material that makes it into a Living Building must pass through a kind of obstacle course. Was it sourced within a certain number of miles from the project site? What are the embodied carbon impacts? Are there chemicals of concern present? Has it qualified for a Declare Label or the Living Product Challenge? If it contains wood, was that wood certified by the Forest Stewardship Council?

Then, of course, there is the famous Red List. With very few exceptions, products containing any of 18 groups of highly toxic chemicals are barred from any LBC project. There is good reason for this. With more than 85,000 chemicals in use today, the building and consumer products markets have suffered from decades of non-existent regulations — leading to widespread exposures.

Nearly everyone on Earth has traces of some of the Red Lists chemicals in their bodies — forever. These toxins persist in the environment, passing across the food chain and contaminating humans, animals and ecosystems across the globe.

The Red List Imperative (within the Materials Petal) seeks to change the market in two significant ways: provide transparency for product ingredients and encourage the replacement of chemicals of concern with safer alternatives.

On a global scale, things aren’t changing fast enough. But the Red List Imperative is working. Since my first Living Building project 10 years ago, the market has gone through a significant transformation. Early on, no manufacturer had heard of Living Building Challenge, let alone the Red List. Today, there are thousands of products with Declare Labels or Health Product Declarations, or that provide full transparency of their ingredients in some other fashion. There are hundreds of manufacturers that have eliminated Red List chemicals from their products, often improving them and lowering costs in the process.

Over those 10 years, I’ve also learned that it’s crucial to bring order early on into the selection of products and materials. One of the most significant steps we took as a team on the Kendeda Building was to create a comprehensive decision path that helped us address any questions with thorough vetting, due diligence and documentation. Laying out that process during the design phase allowed us to be consistent with materials challenges that arose, whether during design or construction.

Each Living Building project can point to its own successes in working with manufacturers that want to make positive changes for their products. Often these changes have a lasting impact on the product line. The Kendeda Building is no different. One of our numerous successes was with Kawneer, a manufacturer of storefront and curtainwall systems based in metro Atlanta. Kawneer’s work on the Kendeda project helped the company remove Red List ingredients from the curtainwall systems that were used on the building. The company took an additional step by providing Declare Label documentation for many of its products to promote transparency.

The Kendeda project also drove change for other products and their manufacturers. But it is difficult to find an impact more significant than the team’s reliance on responsibly managed wood for the primary structural material.

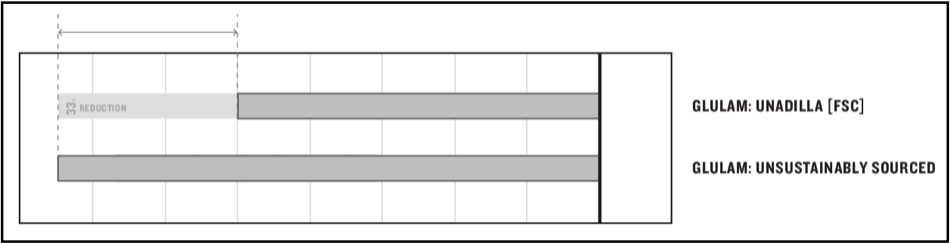

Mass timber helped us address the Material Petal’s Embodied Carbon Footprint Imperative (which falls under the Energy Petal’s Net Positive Carbon Imperative in the LBC’s recently released 4.0 version). It requires projects to account for the embodied carbon emissions from materials and construction, and to purchase carbon offsets to make up for the net embodied carbon. Glue-laminated timber and nail-laminated timber, half of which was salvaged, were among the many material choices that substantially reduced the building’s carbon footprint below such conventional materials as steel, resulting in a lower requirement for carbon offsets.

It wasn’t just the choice of wood that drove embodied carbon calculations down; it also was the source of the wood. The Material Petal’s Responsible Industry Imperative looks to go beyond impacting a single product. The aim is to transform major sectors like stone and wood to use more responsible extraction and processing. When it comes to wood, we know the global gold standard to be Forest Stewardship Council certification. FSC has unmatched standards around harvest, prevention of chemical sprays, preservation of land and focus on indigenous rights. Recent studies have made clear that land disturbances from logging can release significant amounts of carbon from the soil itself, so wood that is not harvested to FSC standards doesn’t sequester as much carbon.

While the design team recognized the environmental benefits of responsibly harvested mass timber from the start, the selection of FSC wood was not without controversy. State politics allowed a law to be enacted that prohibits state-funded facilities from relying on any green building certification system that recognizes only FSC-certified wood. Because the Kendeda Building is funded by a private grant, however, Georgia Tech was able to take a stance for ecological restoration and protection of our renewable resources by choosing responsibly managed FSC wood. With the building’s primary structure of columns and beams of glue-laminated timber and a nail laminated timber flooring and roofing (50 percent which is reclaimed), Georgia Tech has not only showcased a responsible material but also significantly reduced the embodied carbon footprint for the building. The visual warmth and biophilic responses from a natural material are an added benefit.

The Kendeda Building achieved much more than can be described here by advancing the use of sustainable materials. Additional examples range from creative use of reclaimed products to a robust material conservation plan that cut landfill waste by more than 90 percent. These achievements are made even more noteworthy by the uniqueness of the building’s regional location. We know that Living Buildings are possible. They are necessary. And in the southeastern United States, they will now be coming in great numbers because of Kendeda’s leadership at Georgia Tech.

Chris Hellstern, AIA, LFA, LEED AP BD+C, CDT, is the Living Building Challenge services director at The Miller Hill Partnership in Atlanta. He’s served on the project team for two certified Living Buildings and several more currently in design and construction. He also co-founded the Healthy Materials Collaborative. The author of several professional journal articles, Hellstern volunteers with local school groups to mentor students about sustainable practices. As an affiliate instructor at the University of Washington, he currently is teaching a graduate course on sustainability.

PHOTO AT TOP OF COLUMN: Ceiling panels installed before dry-in phase. Photo by Matt Kikosicki.