As part of their research into the location of the Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design, the design team studied the environment of the site and uncovered old maps that shed light on changes over the years.

But the building site’s ecological history is connected to the ecological history of a much broader area — and the impact of regenerative projects like Kendeda Building may model how to restore the natural well-being of an entire region.

The detailed cartography goes back only so far. But we do have an idea of what was on the Kendeda site before Europeans arrived, and how that 1.3 acres — located at what is now just northwest of the corner of State Street and Ferst Drive on the Georgia Tech campus — interacted the surrounding ecosystem.

It almost certainly was part an extensive mixed-hardwood forest — a patch of Georgia Piedmont that sloped down and rolled north toward a little creek gully. Rich organic soils — built up from centuries of plant and animal life in a wet, warm climate — were layered over a clay substrate.

As far as we know, Native Americans didn’t have a settlement close by, which likely means that these woods wouldn’t have been purposefully burned by local Creek tribes (the Creeks were known to set fire to woods to encourage game and to make room for agriculture). The nearby stream flowed northwest, where it merged with other branches and eventually flowed north into Peachtree Creek and then the Chattahoochee River.

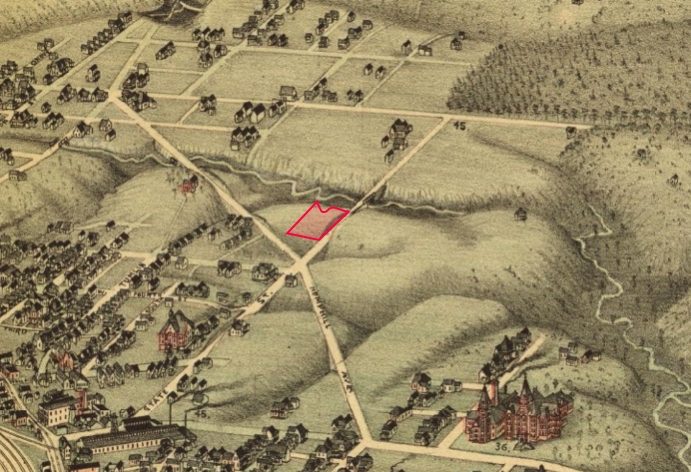

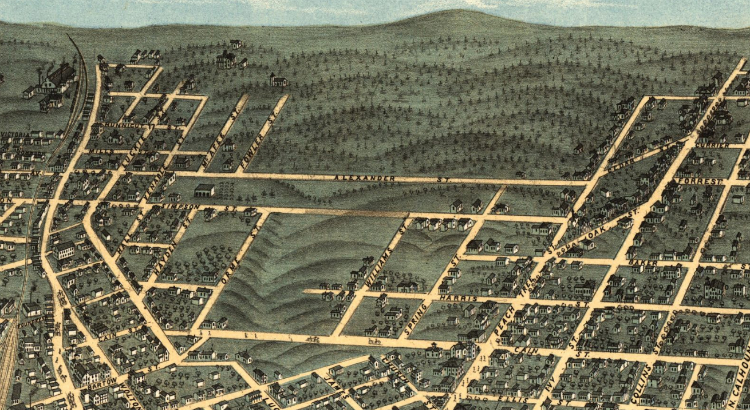

By some point in the 19th century, the larger area that is now the northwest quadrant of the Georgia Tech campus had been cleared — presumably by settlers and their slaves. Above, I’ve outlined the Kendeda project’s approximate location in red on a detail I pulled from this awesome 1892 bird’s eye map of Atlanta. Tech Tower, now the university’s architectural icon, was already four years old at the time, and the other red brick buildings on the tiny Georgia Tech campus huddled tightly around it (bottom right of the image). A few dirt roads led north into what appear to be pastures or cropland.

The lack of tree cover would have begun the process of eroding those forest soils — evidenced today by the how close that Georgia red clay is to the surface. A cut along State Street (on the site’s eastern edge) shows that people had begun to carve into the land a bit, and State Street itself crossed the still free-flowing creek via a bridge.

More dramatic landscape changes came early in the new century. Most of the territory in the quadrant shown above was incorporated into the City of Atlanta in 1910. Around the same time, a massive sewer upgrade took place across Atlanta — at the then startling price tag of $1.35 million. Among the major projects was the Orme Street trunk line, which carried a combination of street runoff and household sewage northward, away from the city, to empty into Tanyard Creek. The small natural stream north of the Kendeda site remained free flowing but now it emptied into the Orme Street line, which diverted its waters directly north toward Tanyard Creek.

It’s not clear whether the stream eventually washed underground into the Orme Street sewer or still merged — as it before Europeans arrived — directly into South Peachtree Creek. But it already was clear that the new line was sending badly polluted water into Tanyard Creek. As a 1909 article in the Municipal Journal and Engineer put it in the caption to a photo: “The flow is composed entirely of very strong household waste.”

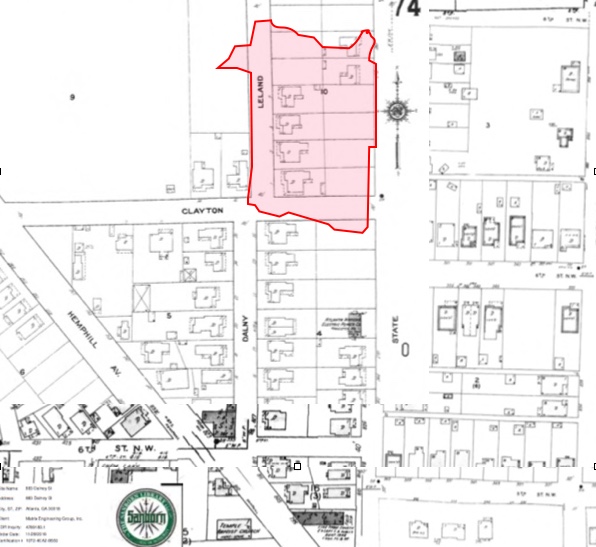

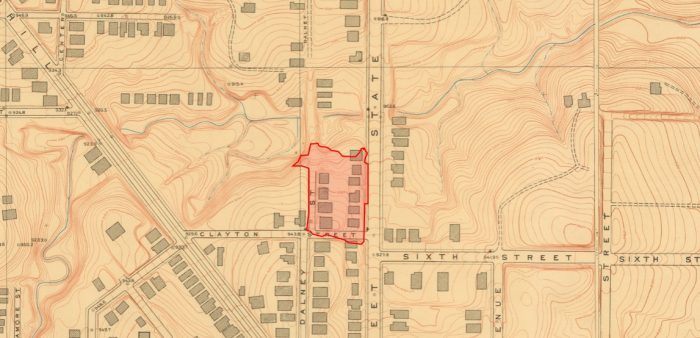

A 1911 Sanborn Fire Insurance map (a portion of which appears above) shows that the area between State Street and Leland Street (later to be renamed as an extension of Dalney) had been platted and already included six small houses. The growing neighborhood was part of “Chastaintown” — named after Avery Chastain, who owned a estate nearby at Hemphill and 10th Street. According to various histories of the region, Chastain was the main landowner in the area to the north and was responsible for its early development. A topographical survey by the city (below) indicates that, by 1928, 11 houses had been built on what is now the Kendeda site.

The small creek in the nearby ravine still saw daylight, for the most part. But portions of land around the ravine had been graded and two small sections of the stream (just north of the Kendeda site) were now piped under State Street and what by then was renamed Dalney Street.

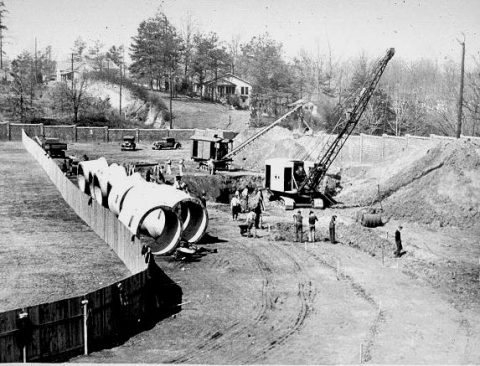

Those pipes presaged a much more extensive creek burial. Kendeda Building project architect Joshua Gassman of Lord Aeck Sargent believes the creek north of the site was covered shortly after 1928. I think I’ve pinpointed the time a bit more closely: As part of the New Deal, the Work Projects Administration funded a major expansion of Atlanta’s sewers. Construction took place in 1935 and 1936. That citywide upgrade included improvements along the Orme Street line and its feeders. The line itself was extended northward, so the point at which Tanyard Creek first saw daylight moved northward as well. Branch lines — of the sort that would bury the unnamed creek that drained the Kendeda Fund site — were also constructed.

The extensive storm sewers marked a significant ecological change for the growing Georgia Tech campus and the surrounding area. By World War II, almost all surface streams in Midtown Atlanta had been piped and buried. The hard surfaces that rushed water into those sewers deprived the soil of moisture that naturally replenished plants and animals. Burial of the creeks eliminated habitat for fish, amphibians and waterfowl. And replacing the slow steady flow a natural creeks with the rush of water through a network of pipes exacerbated downstream flooding.

These were also “combined sewers.” They whisked away both household waste and surface runoff, creating a whole new set of problems downstream. The expanded Orme Street tunnel took in spilled oil from every gas station across a large swath of Midtown, detergent from every washing machine, and the flushes from every toilet. In dry weather, that wastewater was routed for miles underground, toward the city’s giant R.M. Clayton wastewater treatment plant on the Chattahoochee. For decades, however, even small amounts of rainfall would overwhelm the system — sweeping the untreated waste over small berms inside the pipes.

Tanyard Creek was recipient of that waste from most of the Georgia Tech campus and West Midtown. Not surprisingly, the stench and bacteria levels were off the charts. The habitat was more conducive to rats, mosquitoes and algae than to mallards, dragonflies and water lilies.

In two separate purchases during the 1960s, the Georgia Tech campus expanded to incorporate much of old Chastaintown. It became an expansion zone on the edge of the campus. Most of the bungalows on what was to become the Kendeda site were razed and replaced with an asphalt parking lot.

The conversion was complete: In less than 100 years, a complex forest eco-system that had fed a natural watershed had become the simplest of surfaces — an asphalt parking — that washed rainwater (and whatever the rainwater happened to pick up along the way) into a pipe.

This is a beautiful trip back in time. Thanks for compiling all the research!