Solar panels may shimmer in many a mayor’s eyes as cities commit to 100 percent renewable energy. When they get down to the nuts and bolts, however, they’ll find that efficiency gets them most of the way to their goal.

“The biggest opportunity is going to be in the boring stuff,” says Mandy Mahoney, a former City of Atlanta sustainability director who’s now president of the Southeastern Energy Efficiency Alliance.

That’s likely to mean a boost for such basic tasks as energy audits, updating controls, tightening building envelopes and improving operations — particularly at city water works and other big-ticket municipal energy users.

The drive toward running U.S. cities entirely on renewable energy has blossomed into a national movement. Last week, Columbia, S.C., became the 36th city to pass a local ordinance setting a timeline to go all-renewable. And on Monday, some 250 mayors closed out the annual meeting of U.S. Conference of Mayors by unanimously approving a resolution calling for more cities to make the transition.

Media coverage inevitably focuses on the supply side of the equation — illustrated, of course, by photogenic photovoltaic panels. And unique circumstances may cause some cities to rely mainly on the generation of renewable electricity.

Las Vegas illustrates the point. The fast-growing Nevada city recently announced that it became the first large municipality to run its own operations entirely on renewables. It helped that the Nevada city is close to Hoover Dam — one of the nation’s biggest hydroelectric plants — and in a desert that’s attracting large solar farms

Solar and wind also are likely to play a particularly large role in California cities, where clean energy incentives abound and the entire state may soon commit itself entirely to renewable energy by 2040.

For most cities, however, reducing energy demand will almost certainly play a far larger role than increasing renewable energy supply. That’s particularly true in the Southeast —where the physical climate is hospitable to solar, but the political climate is less congenial.

In Georgia, the dominant utility sources less than 2 percent of its electricity from renewable sources. In response to a court settlement with environmental groups, the state Public Service Commission is pressing Georgia Power to increase that number. Last week, the utility announced plans to add 900 megawatts of solar production and 300 MW of wind to its portfolio.

Such a small supply could limit the amount of renewable energy that the city is able to purchase via renewable energy credits, which amount to the tool of last resort for entities that are trying to eliminate their dependence on fossil fuels. Additionally, the state’s Territorial Electricity Act protects Georgia Power’s monopoly within its service region by severely limiting the ability of both private and public customers to generate and use their own renewable energy across multiple properties.

“Anything that we would do that would be utility scale would have to go through Georgia Power,” says Chief Atlanta Resilience Officer Stephanie Stuckey.

Atlanta already is taking steps toward powering its own buildings with solar. According to Stuckey, city officials may finally sign contract next month to place 1.5 megawatts worth of panels on the roofs of 24 city buildings.

But Stuckey efficiency to be a far larger part — perhaps 80 percent — of the mix. Even before City Council mandated all-renewable push, her office had contracted with four energy service companies (better known as ESCOs) to audit nearly 100 city-owned buildings for energy-saving opportunities. The next step is to work with the ESCOs to come up with an energy service contracts that, in effect, finance the efficiency measures with savings that accrue from lower energy bills.

Everyone seems to agree that the lowest hanging fruit for big energy savings is at the city’s wastewater and water treatment plants. The water system uses around one-fourth of the city’s total energy — including the extremely wasteful practice of “flar ing off” of the methane gas that’s a byproduct of sewage treatment.

Another big target is likely to be the world’s busiest airport, which is in the early stages an enormous renovation that’s expected to enhance its existing LEED green-building certifications. The airport already has taken such steps as switching over to all-LED lighting. Despite those efficiencies, the airport remains responsible for another quarter of the city’s electric bill.

All those opportunities only exist under the shadow of an enormous challenge. The resolution mandating the switch requires Stuckey’s office to come up with a plan by the end of the year to get the city’s operations to 100 percent renewable energy by 2025. As if that’s not enough, the plan must include ways to get the entire city — private buildings, as well as city operations — to 100 percent renewable by 2035.

Stuckey argues that Mayor Kasim Reed’s strong support for her office’s mission, as well as apparent unanimous support for the 100 percent goal by the leading mayoral candidates, bodes well for the effort. Reed will be replaced by his successor in January 2018. One encouraging sign: City officials have given Stuckey the go-ahead to negotiate with a consultant “to help us work through the numbers.”

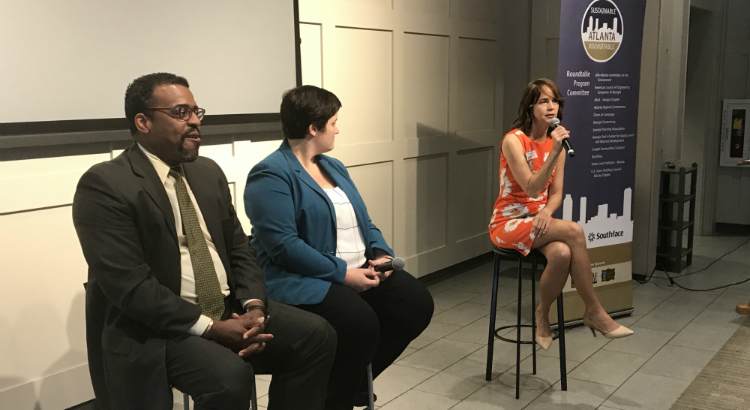

Photo above: Stephanie Stuckey (right) and other officials spoke about the city’s renewable energy goal in May at the Sustainable Atlanta Roundtable. Photo by Ken Edelstein.