This article was first published in the Chronicle of Philanthropy and is republished with its permission.

Before the Olympian Roger Bannister shocked the world in 1954, it was widely considered impossible for a human to run the mile in under four minutes. Mr. Bannister proved otherwise. Incredibly, just 46 days later, John Landy beat his record. In the decades since, more than 1,400 other runners worldwide have run sub-four-minute miles, including nine high-school athletes in the United States. The record is now 3:43.13, almost 17 seconds faster than “the impossible.”

The moral? Everything seems impossible until someone does it.

Unlike public corporations, foundations are not accountable to shareholders or investors. The U.S. tax code entrusts them with a pool of tax-advantaged money and an expectation that they will use it to help advance the public good.

We see evidence of philanthropy’s efforts to do just that on a daily basis — from the campaign for marriage equality and the defense of immigrants’ rights to fighting childhood obesity and expanding college access for all. Because of the federally subsidized tax benefits foundations receive, they have a special responsibility — and the wherewithal — to step out and take risks in areas where business often fears to tread.

However, one notable area where foundations have missed an opportunity is the way they manage real-estate investments and capital grants.

Virtually every foundation has a portion of its diversified portfolio invested in real estate. An overwhelming majority of those assets today are in real-estate investment trusts and mutual funds, holding conventional strip malls, office buildings, and multifamily dwellings that waste, on average, three-fourths of the energy they use. They are similarly wasteful with water and pollute the earth with toxic materials that often threaten the health of their tenants. They may be “safe” investments, but they do nothing to make the world a better place.

So, too, with capital grants, which are commonly directed toward endowments, buildings, or equipment. Research labs, libraries, and performance halls routinely raise vast sums from foundations, yet donors to those projects rarely use the investments as opportunities to push for higher levels of environmental performance. While some foundations encourage basic green design, many projects fall woefully short when it comes to addressing water and resource scarcity, eliminating toxic materials, or ensuring equal access to people from all economic circumstances.

Now imagine the alternatives:

- An office building in a walkable, diverse neighborhood with solar panels that generate more electricity than the structure consumes and large operable windows to replace the need for depression-inducing fluorescent lights.

- A research center on a bustling college campus built with wood from responsibly managed forests that also captures and treats rainwater for all uses.

- An affordable-housing complex that reduces asthma symptoms for children through proven, healthy design guidelines.

Buildings with these features exist already — fully occupied and producing net incomes that often rival or beat conventional projects on a per-square-foot basis. Moreover, they serve as models for how to embed values of fairness, conservation, health, and happiness into communities nationwide.

The foundations where we work can attest to this.

The four-year-old Bullitt Center in Seattle stands as one of the world’s greenest buildings and is challenging the way the world thinks about sustainability. Certified to the Living Building Challenge — the most ambitious measure of sustainability in construction — it is also a cornerstone of the Bullitt Foundation’s endowment. Ninety percent of the building has been leased to conventional, commercial tenants, generating financial returns in perpetuity. (The remaining 10 percent is leased to the foundation itself.) Significantly, the construction cost of the Bullitt Center was less than the median for Class-A office space in Seattle.

The Bullitt Center is hardly alone. At Georgia Tech, a project funded by a $30 million grant from the Kendeda Fund will apply the same Living Building Challenge in the warm and humid southeast, requiring alternative design thinking, new materials, and different equipment than in the Pacific Northwest. Kendeda is documenting this Atlanta project closely in an effort to demonstrate how ambitious sustainability goals can be met in radically different climates. It will also expose generations of students at an outstanding engineering university to cutting-edge building technology.

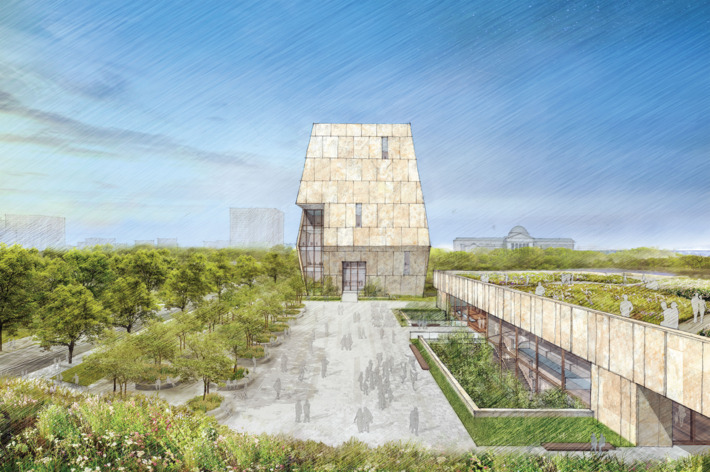

The Obama Foundation has announced that the Obama Presidential Center in Chicago “will, at a minimum, be LEED v4 Platinum” — the U.S. Green Building Council’s highest rating for energy and environmental design — “and we are exploring the possibility to surpass those qualifications.”

Presidential libraries have special security concerns that present architectural limits, but it should be possible for a building in Chicago to generate more energy than it consumes, and it is certainly possible to construct a wholly nontoxic building. This will be a highly visible, precedent-setting structure in yet another wildly different, challenging climate. And it, too, will be underwritten by a foundation.

Other foundations have advanced green buildings in many important ways. In 2003, the Kresge Foundation began to challenge nonprofits to build and remodel their facilities to LEED standards. In 2012, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation moved into its new headquarters in what is now the nation’s largest “net-zero energy” certified office building.

These examples demonstrate what’s possible. But they are noteworthy largely because they stand out from the norm. In 2017, they should be ordinary and normal.

Make no mistake: Using direct grant making to support things like scientific research, environmental advocacy, climate mitigation, or alternative energy is important. But foundations have an opportunity to do even more for the environment through their facilities projects, promoting truly regenerative design and creating positive examples of the world everyone should be building.

Consider the Ford Foundation recent commitment to make $1 billion in mission-related investments over the next decade. Imagine if those investments in affordable housing included a commitment to screen out all toxic materials, generate as much energy as residents use, and filter rainwater for drinking. That would save money over five to 10 years; provide much healthier, more comfortable residences; and sharply reduce the global-warming footprint. Many will consider this a “radical” suggestion; in truth, it is common sense.

As foundation boards and leaders weigh capital grants and investments in real estate, they should keep in mind the lesson of Roger Bannister and John Landy. By creating facilities that meet the Living Building Challenge, we have already surpassed the architectural equivalent of the first four-minute mile.

Now we need to make such buildings the new normal.

Denis Hayes is president of the Bullitt Foundation and was the national organizer of the first Earth Day. Dennis Creech is a fund adviser to the Kendeda Fund and co-founded the Southface Energy Institute.