Net zero energy schools are gaining ground in the darnedest of places.

According to the New Buildings Institute, four of the five states with the most net zero energy schools underway in 2016 were in the South — even though high humidity, low power rates, and few green carrots and sticks would seem to make net zero a steep climb in the region.

In South Carolina, there’s a county system planning five net zero facilities. A North Carolina district has committed to building only net zero from now on. And in Virginia, Arlington Public Schools is operating one of the nation’s largest net zero buildings of any kind.

“Net zero wasn’t even part of the [Arlington Schools] proposal,” Discovery Elementary School architect Wyck Knox said before collecting an award at last month’s U.S. Green Building Council’s Green Schools Conference in Atlanta. “We looked at it, and said, ‘You know, we think that we can do this at net zero energy and still stay under-budget.’”

It helped that Knox, who practices at VMDO in Charlottesville, Va., was pitching his ambition to a system with a strong sustainability track record. At least five of Arlington’s schools have achieved LEED certification.

That track record includes data collection. For example, the district already had benchmarked the energy use intensity of its elementary schools at 68. That gave VMDO and CMTA Consulting Engineers — a Kentucky firm that specializes in high-efficiency projects— a better idea of an achievable energy target. They opted to model the new school at one-third the elementary school average.

In its bid for the 98,000-square-foot project, VMDO presented Arlington with a choice. Either contract for a “net zero ready” building (in other words, without the solar component) for $30.7 million, or contract for the same building but spend another $1.3 million on nearly 500 kilowatts worth of solar panels. As it turned out, both bids were well below the system’s $36 million budget.

“We didn’t make a big deal about it,” says John Chadwick, assistant superintendent for facilities and operations. “We didn’t even present [the net zero potential] to the board. It just ended up flying in under the radar.”

Turning a corner

Net zero energy can be mean slightly different things to different people. Generally, a building meets the definition if, through a combination of efficiency and onsite renewable energy, it produces as much energy over the course of a year as it uses. If it produces more clean energy than it uses, it’s net positive.

In 2016, the feasibility of net zero K-12 schools seemed to turn a corner. The New Buildings Institute’s list of “verified” and “emerging” net zero buildings reached 332 projects in November — an increase by three-quarters over 12 months. Thirty-eight percent of those buildings were K-12 schools.

“We used to have arguments about whether it was technically feasible,” says NBI’s Amy Cortese. “That conversation is over.”

Cortese is careful to note that net zero (which NBI refers to as “zero net energy”) isn’t a slam dunk for more energy-intensive building types, such as hospitals. But schools — particularly elementary and middle schools — are a good fit for a number of reasons.

On the demand side, they fully operate only nine months of the year and for limited hours. Access is relatively controlled. Occupancy levels are predictable and constant, and after hours only partial. Aside from computers, there aren’t a lot of high-intensity plug loads.

On the supply side, schools play to the strengths of solar. They’re usually one or two stories— providing a big footprint for photovoltaic panels relative to the square footage inside. Plus, most demand comes during the day, when the sun generates electricity.

School districts also are owner-occupants. So they have a longterm interest in reducing utility expenses, and they usually possess bonding authority to fund long-horizon projects.

Finally, there’s the mission: Educating children. A building’s sustainable features offer up a teachable model for both the environment and technology. The most creative design teams draw out those themes by employing nature-based motifs and by engaging students with energy dashboards and observable systems.

“In many circumstances, [net-zero] can be done for the same cost as a conventional building, and once they’re in place, they save every year on utility costs,” Cortese says.

The opportunity for more ambitious school energy goals hasn’t gone unnoticed. Last Fall, the U.S. Department of Energy established a Zero Energy Schools Accelerator to offer technical support and to encourage partnerships among districts, designers and builders. It’s unclear how the accelerator will fare under Energy Secretary Rick Perry, but the overall momentum seems likely to continue regardless of federal support. As if to underscore that point, last week’s USGBC Green Schools Conference spotlighted the nuts-and-bolts of implementing net zero.

Premium costs and inadequate technology no longer seem the highest hurdles. Nowadays, the real challenges often are internal. Administrators, key personnel and even parents and other stakeholders often are skeptical of radical change, according to facility planners with experience on net zero projects.

San Francisco Unified School District Sustainability Director Nik Kaestner admits that the Bay Area’s mild climate and eco-friendly politics give him some advantages. But he also confesses to the challenge of bringing along an operations and maintenance staff that’s used to standard procedures on conventional equipment.

“They love their boilers,” he quipped to an audience at the Green Schools Conference. “Now, we’re asking them to deal with much more responsive systems.”

The rules are changing

Once a project is approved, net zero designers typically follow a rule of thumb: Before sizing renewables, they do everything possible to cut their projected energy demand. Or as Reilly Loveland (a colleague of Cortese at the New Buildings Institute) puts it: “You have to eat your efficiency vegetables before you move on to the cake.”

The admonition is well-founded. Installing more PV panels usually costs a good deal more than making the building more efficient.

Discovery School’s designers followed the eat-your-vegetables rule — up to a point. They studied the building’s orientation and massing to maximize passive solar. They created a tight envelope by using insulating concrete forms and, Knox says, through “an obsessive attention to detail.” They “did a lot” of energy modeling. They followed CMTA’s recommendation to heat and cool the building with 58 geothermal heat pumps, which effectively broke the school down into sensor-controlled zones — each serving about two classrooms.

At the same time, solar’s plummeting costs and improving efficiency have begun to disrupt the vegetables-before-cake menu. Knox describes one example: When he learned it would take $119,000 to upgrade all Discovery’s windows from two panes to three panes, he asked CMTA what it would cost to up-size the solar to adjust for sticking with double-pane windows. The answer: $9,000.

“Adding the panels was a no-brainer,” Knox says. Still, he advises, “95 percent of the time, conservation’s going to be the way to go.”

Another net zero maxim isn’t likely to change any time soon. It’s the idea that owners and occupants ultimately will decide whether the building is a success or not. As San Francisco’s Kaestner stressed, that starts with the operations and maintenance staff. But it extends to principals and teachers. If teachers aren’t fully vested partners in a school’s sustainable aspirations, there’s a risk of blowback over seemingly minor issues, like losing control of the thermostats in their classrooms. The energy manager for a Tennessee school district at the USGBC conference even suggests a small concession to get buy-in: Allow teachers to bump set temperatures up or down by 2 degrees.

“A little freedom,” he says, goes a long way.

Lessons learned

The ultimate “customers” for any school are, of course, its students. Knox was acutely aware of that fact as he and his team designed Discovery Elementary. As a result, environmental awareness is reinforced throughout the building. Each grade’s classrooms are built around a common hallway with a way-finding motif built on broader and broader realms of nature. Kindergartners are “Backyard Adventurers.” First graders are “Forest Trailblazers.” And so on, all the up to fifth grade “Galaxy Explorers.”

There’s also a very active Eco-Action Team. At the front entrance, a spiffy, modern solar calendar tracks seasons. There’s even a Solar Lab, where students are able to interact with the school’s rooftop electric and water systems. Making the building’s systems transparent went hand-in-hand with putting sustainability front and center.

“Once you start the process of asking ‘how can we do this better?’, it becomes contagious,” he says. “Net zero is an easily measurable sustainability goal. Once we started working towards that, the students and teachers took it to the next level by starting programs to measure and track their trash, food donations and modes of commuting to school. It’s simply in the DNA of the school. Building-as-teaching-tool features just help reinforce that culture.”

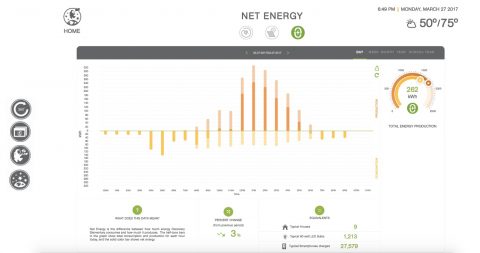

CMTA’s Devin Cheek is particularly proud of the school’s energy dashboard. After an off-the-shelf product crashed, he and his team devised a custom dashboard that tracks the energy production, energy consumption and the net of those two numbers. In addition to accessing it real-time from any computer, students can view the dashboard on a large-screen TV in the entrance lobby and on a waterproof version in the rooftop solar lab.

It helps that the dashboard consistently shows good news. Discovery’s performance since it opened in Fall 2015 has exceeded expectations. Knox credits a lot of factors but points particularly to the tight building envelope. At first, the building wasn’t net positive, but that was because the solar panels weren’t installed until January 2016. Performance improved even more after the summer, when the building was fully commissioned.

This school year, both Knox and Cheek have taken to looking gleefully at the dashboard and proclaiming — with guarded optimism — that Discovery’s 2016-17 school year could “blow net zero out of the water.” Even the winter months ran net positive. This year, the school is expected to save the district some $80,000 in power bills (compared to the typical Arlington Elementary), and that number is likely only to get better.

Similar stories at other net zero schools appear to be building momentum for the net zero movement. Knox points to net zero projects popping up in Maryland that are looking to the nearby Discovery Elementary for inspiration.

Similarly inspired by a net positive school in Sandy Grove Middle School in Lumber Bridge, N.C., the Horry County, S.C., school board committed last year to five net positive projects: three new middle schools, an intermediate school and an elementary school. The smallest of those five schools — which were designed by SFL+A of Raleigh, N.C., and are scheduled for completion this summer — will be 120,000 square feet.

Ground zero for net zero schools is, of all places, coal-rich Kentucky, where then-Gov. Steve Beshear tapped federal stimulus money to offer incentives for schools to become more energy efficient. CMTA, the Kentucky-based engineering firm that worked on Discovery Elementary, owes much of its net zero expertise to that initiative.

The solar costs for those early projects bring into focus how photovoltaics have changed the game for net zero. Richardson Elementary School in Warren County was completed in 2010. It has a 348 kilowatt system that cost $2.75 million, for an installed cost of nearly $7.90 per watt. Five years later, Discovery’s 496 kw system ran $1.3 million, or $2.62 a watt.

For the Arlington system’s Chadwick, the progress is tantalizing. Those spanking new net zero schools are one thing, but he notes that most schools were built years ago, and they’re currently not net zero.

“It’s much easier to do this on a new building,” says the sustainably minded facilities chief. “The next frontier is how we can do it on an existing building.”